LILLIAN: So you were an accidental Trotskyite, just as you were an accidental Mrs Wilson. Just out of curiosity, what decisions in your life did you actually make?

MARY: What I believe is that the the decisions we agonize over are often the most insignificant - what to have for dinner, beef or chicken. What color to make the rug. But the big things almost seem to choose you. I was like "Stendahl's hero, who took part in something confused and disarrayed that he later learned was the battle of Waterloo." I had no idea that I was making the most important decision of my life - to be serious, to be involved in public affairs, to be an intellectual. And I had no idea that I was choosing not just to be a Trotskyite but to be an anti-communist.

And from a study guide we learn:

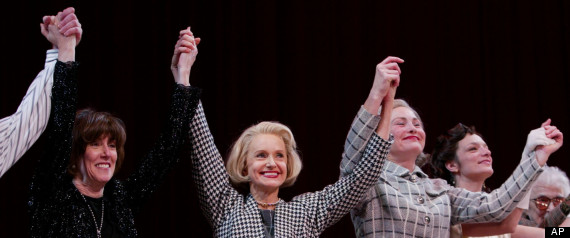

"Lillian Hellman and Mary McCarthy had been feuding ever since they met at a writer’s conference at Sarah Lawrence College in 1948. In 1980, McCarthy delivered the cruelest blow when she declared in a television interview with Dick Cavett that “every word [Lillian Hellman] writes is a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the.’” This comment prompted Hellman, who was watching the interview, to bring a slander suit against McCarthy. Nora Ephron’s play, Imaginary Friends, which opened on Broadway on September 29, 2002, focuses on this lawsuit and the feuding that lead up to it.

Their bickering stemmed from, as Ephron notes in her introduction to the play, “McCarthy’s love of the truth—which she turned into a religion—and . . . Hellman’s way with a story, which she turned into a pathology.” InImaginary Friends, Ephron imagines a final meeting between the two women, in Hell, as they assess their lives and their antagonistic relationship through a series of razor-sharp verbal attacks on each other. Lisa D. Horowitz, in her review of the play for Variety, writes that Ephron’s Hellman and McCarthy “prove, quite entertainingly, that they are each other’s own special hell.”

Imaginary Friends Summary

Act 1

The play opens on a bare stage where two women, Lillian Hellman and Mary McCarthy, are smoking. They try to recall if they had ever met, but soon admit that they were both at Sarah Lawrence College in 1948, when the two were invited to a writers’ conference there. McCarthy remembers being incensed at what she considered Hellman’s lies about the Spanish civil war. She interrupted and corrected Hellman, and the two began to argue.

Hellman shifts the focus to her speech to the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1952. She recalls how she refused to identify communists by insisting, “I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions,” her most famous quote. The two women then bicker over details of Hellman’s past and discuss other female writers. They conclude that no one reads either of them anymore.

Their conversation turns back to their personal feud, which culminated in Hellman bringing a slander suit against McCarthy for declaring in a television interview with Dick Cavett that Hellman likens their situation to a story about two U-boats who engage in battle.

The next scene jumps to Hellman’s childhood in New Orleans. Hellman plays herself as a child and reminisces about her happy experiences growing up. When she sees her father in a passionate embrace with Fizzy, a young neighbor, she falls out of the tree she had been climbing. Her nurse Sophronia comforts her and extracts a promise that she will tell no one about her father’s indiscretion.

The scene changes to Minneapolis, where McCarthy and her siblings moved after her parents died. McCarthy recalls that no one actually ever told them the truth about her parents’ death. They were sent to live with a great-aunt and her new husband, Uncle Myers, who physically abused her."

No comments:

Post a Comment