1962 International Writers Conference, Edinburgh: an edited history

Written by Drs Angela Bartie and Eleanor Bell, University of Strathclyde

‘People jumping up to confess they were homosexuals; a registered heroin addict leading the young Scottish opposition to the literary tyranny of the communist Hugh MacDiarmid… An English woman novelist describing her communications with her dead daughter, a Dutch homosexual, former male nurse, now a Catholic convert, seeking someone to baptize him; a bearded Sikh with hair down to his waist declaring on the platform that homosexuals were incapable of love, just as (he said) hermaphrodites were incapable of orgasm (Stephen Spender, in the chair, murmured that he should have thought they could have two)… Excerpt from a letter Mary McCarthy wrote to Hannah Arendt describing the 1962 International Writers’ Conference in Edinburgh (28/09/62)

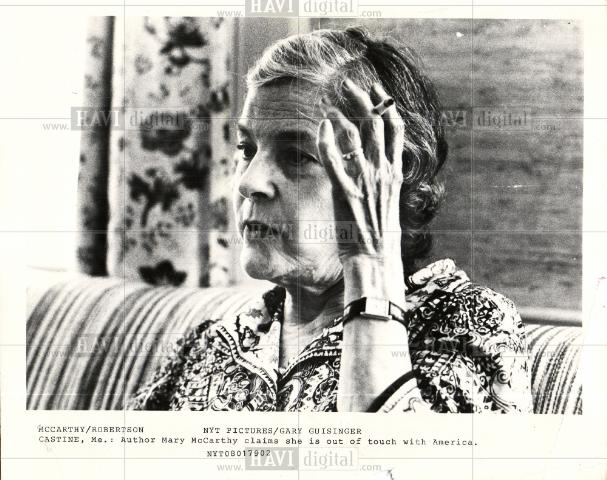

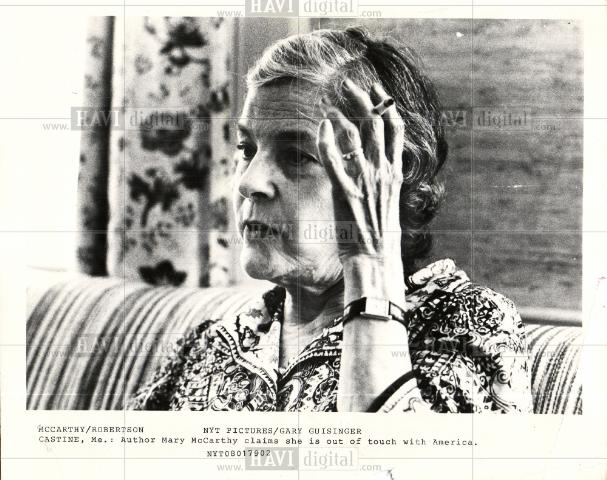

In August 1962, a five-day Writers’ Conference took place as part of the Edinburgh International Festival of Music and Drama. It was organised by publisher John Calder, in conjunction with Jim Haynes (then running Edinburgh’s Paperback Bookshop) and Sonia Brownell (commissioning editor of a publishing house and the widow of George Orwell). Together they produced a line-up of writers that included Americans Norman Mailer, Henry Miller, Mary McCarthy, and William Burroughs, Scots Hugh MacDiarmid, Muriel Spark, Edwin Morgan and Alexander Trocchi, English Lawrence Durrell and Stephen Spender, Austrian Erich Fried, and Indian Khushwant Singh.

This conference attracted a huge audience that filled the 2300-capacity McEwan Hall every day and was reported widely in the media, both at home and abroad. Each of the five days explored a different theme: Differences of Approach, Scottish Writing Today, Is Commitment Necessary?, Censorship Today, and the Future of the Novel. The week before the conference, Calder told the press ‘we are imposing no prohibitions on the free expression of opinion, however controversial or unusual’. The frank discussions of love, sex and homosexuality (as well as drug-taking) at both the Conference and its daily press conferences were certainly shocking. Its impact was felt in many other ways too; not least in the way it effectively launched the career of William Burroughs, who was largely unknown at the time. In Scottish circles, the famous clash between Alexander Trocchi and Hugh MacDiarmid has helped to redefine debates about Scottish national cultural identity. The Conference has also been cited as the starting point for many other large gatherings and conferences (e.g. the Albert Hall Poetry Reading of 1965, which characterized the counterculture in Sixties Britain) and even the existence of the major book festivals that we have today.

In September 1962, John Calder told the Herald that ‘the conference was an experience in adult education. The gamble was to see if we could interest an average public in ideas, the combination of observation and philosophy that compose the writer’s tool-kit. We succeeded because there is a great hunger for education and for an understanding of the world we inhabit.’

Day one: contrasts of approach

Chair: Malcolm Muggeridge

Questions for day one (From original conference programme):

‘In this first discussion novelists will be asked to explain how they approach their work and why they try to write in a certain way. Some novelists are principally interested in the ‘content’ of their novels, in the ideas, the plot and the characters that they create, and regard ‘style’ as less important. Others see style as determining the nature of the content itself. The audience will hear the views of different authors on this and related problems.’

Selected Highlights:

Selected Highlights:In her speech,

Mary McCarthy gives public support for

William Burroughs’Naked Lunch. Burroughs later acknowledges that this support, and his participation in the Writers’ Conference, helped to launch his career. McCarthy also comments ‘With the French novel I think the really – the new novel – is really simply a form of dressmaking… All the French novelists have taken simply to this kind of vogueishness, this couturier novel writing, but I don’t think has much to do with novels – with the novel taken as a serious thing… I would except Nathalie Sarraute from this…’

Colin MacInnes takes issue with Mary McCarthy later. Henry Miller’s writing, he feels, reflects universal issues. His Paris does not reflect man in exile, but man in the world.

Dame Rebecca West totally disagrees with Angus Wilson’s views of tradition – the novel is not as conservative as he has depicted – often it has been radical – e.g. Jane Austen (‘Jane Austen wrote novels in which her manner was that of a perfect lady, but what she was saying was to hell with Samuel Richardson and to hell with Clarissa. She said it like a lady, but the intention was strictly revolutionary.’)

Muriel Spark strongly disagreed with Lawrence Durrell’s points that literature should change people – ‘I think that for a novelist to try and change anybody, for anyone to try and change anybody, is horrible.’

Day two: scottish writing today

Chair: David Daiches

Questions for day two (From original conference programme):

‘What is the strength of Scottish writing today and how is it related to the Scottish literary tradition? Should Scottish writers deal principally with Scottish themes, and if they do, what market do they have outside Scotland? Has there been a Scottish Renaissance in recent years, and how successful have been the attempts to use Lallans as a literary language?’

Selected Highlights:

Selected Highlights:

Walter Keir comments ‘There is hardly any Scottish literature worth talking about… The Scottish writer of the moment… he is far too worried about national identity… Here as far as I can see it, parochial, provincial, you may not know it, but we are attending the wake of Scottish literature.’

Edwin Morganagrees, stating that Scottish writers ‘can use English if they want, and still, I think, very readily express something that is purely Scottish. But they should be interested in what is going on not only in Europe, but also in America.’

Alexander Trocchi famously states that he was right to leave Scotland. The whole atmosphere ‘seems to me to be turgid, petty, provincial, the stale porridge, Bible class nonsense.’ MacDiarmid, whom he has a ‘certain love and respect for’, is nonetheless ‘an old fossil’.

Hugh MacDiarmid retorts ‘MrTrocchi seems to imagine that the burning questions in the world today are lesbianism, homosexuality and matters of that kind. I don’t think so at all. I am a Communist, and a Scottish Nationalist and I ask Mr Trocchi and others, where in any of the literature they are referring to… are the crucial burning questions of the day being dealt with, as they have been dealt with in Scottish literature, if you knew enough about it’ to which

Trocchiresponds, ‘We have been exerting our nationalism in Scotland as long as I can remember, and I am damned sick of it.’

Day three: commitment

Chair: Stephen Spender

Questions for day three (From original conference programme):

‘Should the writers use his work as a platform for his political beliefs or his views on religion and other matters? Many believe that the novelist has a social duty to expose the evils of his time and to convert the reader to his opinions. Others believe that the novelist must be above such problems if he is to create a work of art, although he may be committed outside his work. The problem of commitment divides writers sharply and is one of the principal points of conflict in contemporary literature.’

Selected Highlights:

Selected Highlights:

Norman Mailer noted ‘it was particularly brave and true to his commitment’ for Trocchi to appear in McEwan Hall and attack Scottish writing.

LP Hartleynoted that he preferred the term ‘dedication’ to ‘commitment’, largely due to the political connotations of the latter.

John Amirthanayagan argued that the problem of commitment was artificial – as soon as any writer begins to write as a human being, they are committed.

MacDiarmid announced he was ‘the only fully committed writer present at this conference’.

Khushwant Singhstated that very few writers on the platform had succeeded in putting across their commitment in their writing, also asking that writers ‘become a little more confessional and tell us about their personal commitments – not of their political, and other commitments.’ He put across his own four personal commitments (obsessions): to solitude, to love, to death, and to truth. Having described the relationship between love and the desire to resolve the ‘inner solitude’, he went on to state that love could really only exist between heterosexual couples of the same approximate age: ‘I feel that the sort of love I am talking of is denied to the homo-sexual’.

GK Van Het Reve later responds: ‘As you have just heard from one of the former speakers I cannot experience real love. I think I will have to cope with it – I can only say God forgive people who can dare to say such stupid things’.

Dame Rebecca West later comments ‘I would like to suggest to the organisers of this conference that if they wish to organize another writers’ conference, they should have two conferences going on at perhaps the same time. One a writers’ conference. The other a conference at which people could thrash out whether they were homo-sexuals, or hetero-sexual, or whatever.’

Day four: censorship

Chair: Mary McCarthy

Questions for day four (From original conference programme):

‘Opinions on what may or may not be published differ widely. In Great Britain the censorship laws have recently been revised and previously banned books such as ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’ can now be published. In America there has been an even greater relaxation of censorship and the same applies to many other countries, but there are still others where the trend is towards more censorship. Moral and political censorship will be discussed and writers will say how much censorship they think is desirable and where existing restrictions should be removed.’

Selected Highlights:

Selected Highlights:

Mary McCarthy begins by stating her belief that most writers and audience will be against censorship, and that it is much harder to argue the case

forcensorship than against.

William Burroughs comments that all censorship is essentially thought control, but that the main reason usually given for censorship is ‘the necessity of protecting children’; yet they are ‘already subjected to a daily barrage of word and image, much of it deliberately calculated to arouse personal desires without satisfying them. That is what advertising is all about’. One of the arguments

Norman Mailer cites

forcensorship is that works like those by Miller and Burroughs weaken the young: ‘It makes them sophisticated, it makes them too civilised, it makes them insufficiently warlike…sexual literature, you see, does weaken warlike potential because it tends to drain it.’

Stephen Spender intervenes to comment that he feels the discussion is getting too complicated, that the basis for censorship is that readers can be influenced by what they read; that writers, if they believe that literature does good, should also admit that it does harm; that readers could be influenced by what they read in a book (one example he gives is of a reader of Goethe’s novel

Vortex apparently committing suicide ‘as a result of the suicide of Goethe’s hero’).

Day five: the novel and the future

Chair: Khushwant Singh

Questions for day five (From original conference programme):

‘Many new trends in the novel have appeared in recent years and many types of ‘avant-garde’ novel have established themselves in critical and intellectual circles. Has the traditional novel really written itself out and will the public accept the new trends? Where are these trends leading us and why do so many contemporary novelists appear to create difficulties for their own sake? Will the novel perhaps disappear altogether and be replaced by some other literary form? These questions probe not only into the contemporary novel, but into all aspects of contemporary life and may point towards a solution to many of the problems of our time.’

Selected Highlights:

Selected Highlights:

Raynor Heppenstall notes that ‘junkie sex novel which is very much the American novel of the present… is beginning to feel already a little belongs to the past.’

Alexander Trocchi feels he’s being personally attacked ‘when there is all this mention of drugs and sex’, before arguing that the novel and the painting are old categories that are on their way out, which ‘flourished until the end of the nineteenth century at which time the most vital writers and painters began to feel them as limits other than a source of inspiration. Ergo a spate of experimentation at the beginning of the twentieth century. The fantastic anarchic disorder of modern art and the anti-novel.’

Robert Jungk disagrees with Trocchi, going on to argue that the novelist has failed ‘in this task of trying to make the horrible realities of our life more accessible to everyone… He has failed in developing new visions for a new world and new facts’. Later,

Stephen Spender says, ‘I would like to point out that everything that Mr Trocchi has said has been said in 1905. … I am not saying this maliciously at all, because I have happened to study a great deal of the documents of expressionists [who thought that] the fragmentation of values in the modern world should be reflected by fragmentation in modern writing. This is exactly what the futurists were saying, what people were saying before the First World War. It led to a completely dead end and in fact I think the history of modern literature since 1914-1920 or so is the attempt to recover from this point of view.’

For more on the 1962 International Writers’ Conference, see A Bartie & E Bell, The International Writers’ Conference Revisited: 1962 (Cargo Publishing, 2012).

Photographs (c) Alan Daiches. With permission of the National Library of Scotland and the Daiches Family.

In August 1962, a five-day Writers’ Conference took place as part of the Edinburgh International Festival of Music and Drama. It was organised by publisher John Calder, in conjunction with Jim Haynes (then running Edinburgh’s Paperback Bookshop) and Sonia Brownell (commissioning editor of a publishing house and the widow of George Orwell). Together they produced a line-up of writers that included Americans Norman Mailer, Henry Miller, Mary McCarthy, and William Burroughs, Scots Hugh MacDiarmid, Muriel Spark, Edwin Morgan and Alexander Trocchi, English Lawrence Durrell and Stephen Spender, Austrian Erich Fried, and Indian Khushwant Singh.

In August 1962, a five-day Writers’ Conference took place as part of the Edinburgh International Festival of Music and Drama. It was organised by publisher John Calder, in conjunction with Jim Haynes (then running Edinburgh’s Paperback Bookshop) and Sonia Brownell (commissioning editor of a publishing house and the widow of George Orwell). Together they produced a line-up of writers that included Americans Norman Mailer, Henry Miller, Mary McCarthy, and William Burroughs, Scots Hugh MacDiarmid, Muriel Spark, Edwin Morgan and Alexander Trocchi, English Lawrence Durrell and Stephen Spender, Austrian Erich Fried, and Indian Khushwant Singh. Selected Highlights:In her speech, Mary McCarthy gives public support for William Burroughs’Naked Lunch. Burroughs later acknowledges that this support, and his participation in the Writers’ Conference, helped to launch his career. McCarthy also comments ‘With the French novel I think the really – the new novel – is really simply a form of dressmaking… All the French novelists have taken simply to this kind of vogueishness, this couturier novel writing, but I don’t think has much to do with novels – with the novel taken as a serious thing… I would except Nathalie Sarraute from this…’ Colin MacInnes takes issue with Mary McCarthy later. Henry Miller’s writing, he feels, reflects universal issues. His Paris does not reflect man in exile, but man in the world. Dame Rebecca West totally disagrees with Angus Wilson’s views of tradition – the novel is not as conservative as he has depicted – often it has been radical – e.g. Jane Austen (‘Jane Austen wrote novels in which her manner was that of a perfect lady, but what she was saying was to hell with Samuel Richardson and to hell with Clarissa. She said it like a lady, but the intention was strictly revolutionary.’) Muriel Spark strongly disagreed with Lawrence Durrell’s points that literature should change people – ‘I think that for a novelist to try and change anybody, for anyone to try and change anybody, is horrible.’

Selected Highlights:In her speech, Mary McCarthy gives public support for William Burroughs’Naked Lunch. Burroughs later acknowledges that this support, and his participation in the Writers’ Conference, helped to launch his career. McCarthy also comments ‘With the French novel I think the really – the new novel – is really simply a form of dressmaking… All the French novelists have taken simply to this kind of vogueishness, this couturier novel writing, but I don’t think has much to do with novels – with the novel taken as a serious thing… I would except Nathalie Sarraute from this…’ Colin MacInnes takes issue with Mary McCarthy later. Henry Miller’s writing, he feels, reflects universal issues. His Paris does not reflect man in exile, but man in the world. Dame Rebecca West totally disagrees with Angus Wilson’s views of tradition – the novel is not as conservative as he has depicted – often it has been radical – e.g. Jane Austen (‘Jane Austen wrote novels in which her manner was that of a perfect lady, but what she was saying was to hell with Samuel Richardson and to hell with Clarissa. She said it like a lady, but the intention was strictly revolutionary.’) Muriel Spark strongly disagreed with Lawrence Durrell’s points that literature should change people – ‘I think that for a novelist to try and change anybody, for anyone to try and change anybody, is horrible.’ Selected Highlights:

Selected Highlights: Selected Highlights:

Selected Highlights: Selected Highlights:

Selected Highlights: Selected Highlights:

Selected Highlights:

Courtesy of the AuthorNora Ephron on “The Dick Cavett Show” in February 1971.

Courtesy of the AuthorNora Ephron on “The Dick Cavett Show” in February 1971.