September 30, 1979

( The Missionaries and Cannibals problem is a classic AI puzzle that can be defined as follows:Where are we, then, to place "Cannibals and Missionaries," which its publishers present as "a thriller," in the context of Mary McCarthy's work? She is not the sort of writer who would toss off a book as a lark or a diverting experiment, so why has she done it?

It is clear to me that this, the most political, the least autobiographical of her novels, would have been impossible without her experience of traveling to Vietnam as a reporter. Many of the details of that experience, particularly those about physical fear and communal bonding, find their way into this novel in the accounts of the passengers' ordeal. "Cannibals and Missionaries" is the story, among other things, of a committee of liberals who are hijacked while traveling to Iran to examine the atrocities of the Shah's regime. It speaks, with McCarthy's habitually unsentimental voice, to the problem of witness and political responsibility among nonprofessional men of good will. For McCarthy, terrorism is disturbing in the same way that sexual promiscuity would have been for Emily Bronte: it is political activity without manners, without form; therefore it is incapable of yielding much meaning and is inevitably without hope. In some crucial way, it is not serious: it has no stake in the future.

By a stroke of good fortune for the terrorists in this book, the airplane that they hijack contains not only the liberal committee but also a group of art collectors on an archeological tour. It takes the terrorists a while to realize their luck, but they come to understand that they will be able to put the West in the most vulnerable and humiliating of positions: it will have to prove its devotion simultaneously to Art and Human Life. The terrorists bring the passengers to a deserted Dutch Polder - a model farming community built on land reclaimed from the sea - and say that they will exchange the collect: Helen will be flown out after her Vermeer is flown in; Harold can leave when his Cezannes arrive.

On one bank of a river are three missionaries and three cannibals. There is one boat available that can hold up to two people and that they would like to use to cross the river. If the cannibals ever outnumber the missionaries on either of the river’s banks, the missionaries will get eaten.

On one bank of a river are three missionaries and three cannibals. There is one boat available that can hold up to two people and that they would like to use to cross the river. If the cannibals ever outnumber the missionaries on either of the river’s banks, the missionaries will get eaten.How can the boat be used to safely carry all the missionaries and cannibals across the river?

The initial state is shown to the right here, where black triangles represent missionaries and red circles represent cannibals.)

It is a fascinating situation, and it gives McCarthy the opportunity to speak of a new and terrible phenomenon: "put a terrorist next to a work of art and you get an infernal new chemistry, as scarifying to 'civilization' as the nuclear arm." And the situation of a hijacking allows the writer delicious opportunity to examine character: it's a kind of Canterbury Pilgrimage with machine guns.

One can imagine McCarthy's glee as she made out the passenger list for this ill-starred flight. She introduces us first to Frank Barber, the Episcopal Rector of St. Matthew's, Gracie Square, whom we hate instantly for his attachment to the woolen hats his family's eggs wear as a sign of the number of minutes they have lived under boiling water. This, and his habit of saying, "darn it," at the breakfast table. Next we meet Aileen Simmons, president of Lucy Skinner College, the kind of woman who was once referred to as a "game girl." She is 50, unmarried, devoted to her students and her Arkansas family, politically responsible, in all her actions moderate, and torture to be in the room with. We encounter Gus Hurlburt, a saintly Missouri Bishop, and Senator Jim Carey (who perforce reminds the reader of another silver-haired, poetic Irish Presidential candidate whom we were once exhorted to keep neat and clean for). Then there is Sophie Weil, a New Journalist (her name is unfortunate, and McCarthy, who translated Simone Weil's "The Iliad, or The Poem of Force," might have thought again). And then Victor Lenz, a badly groomed Middle East scholar who insists upon bringing his cat. They seem at first not a riveting bunch, and one is grateful for the arrival of Henk Van Vliet de Jonge, a Dutch member of Parliament, poetic as the Senator, and handsomer.

We wait impatiently for the hijacking, so we can see these characters tested. Of course, some will behave their worst under the stress of danger and captivity. Aileen's manners and perhaps her morals turn out to be the most shocking. When the hijacking first occurs and it seems that only the committee will be captured, she resents the exclusion of the first-class passengers: "Don't you think you ought to tell those people who they are? It's not fair - honestly, it is - for them to be let go while we sit here with a price on our head because some of us, like the Senator, are celebrities.... It wouldn't hurt those millionaires a bit to be held for ransom."

Aileen is surely one of the most annoying women in recent fiction, with her rouge, her dyed hair, her sense of place, "as though the conviction she had of her importance were a religious matter." The Reverend Frank is almost as grating. His relentless and simplistic optimism is an offense not only against the facts but against the mysteries of the human heart as well. "We will be bigger people for it, if we will only let ourselves.... Through this unforeseen contact with our captors, we can be enlarged."

But there are heroes on the committee, two pure, two motley. The pure are the old Bishop and the young Journalist. The Bishop is perfectly good, an innocent who shares his birthday cake with the hijackers. And Sophie has the passionate engagement that differentiates her from two lesser heroes - Jim and Henk, who view the world with a detached, spectator's irony and who, although they are real forces for good, recognize the limits of their moral natures.

|

| I discovered this photograph of MM on a Spanish website |

There are heroes, too, among the terrorists: Ahmed, decent, loyal, innocent as the Bishop; and the Dutch leader of the group, Jeroen, whose doomed life McCarthy examines with great insight. His temperament is artistic: he began his adulthood wanting to "consecrate himself in poverty to the value people called 'art'; by learning, if possible, to make some of it himself." But he gives up sketching in the Rijksmuseum for trade unionism, and then for the Communist Party, which he then rejects for the purer art of terrorism:

"Now art, even the Party kind of making propaganda, lost all interest for him, except in the sense that a deed was a work of art - the only true one, he had become convinced. The deed, unless botched, was totally expressive; ends and means coincided. Unlike the Party's 'art as a weapon,' it was pure, its own justification. It had no aim outside itself. The purpose served by the capture of the Boeing was simply the continuance or asseveration of the original thrust; ransom money, the release of fellow activists, were not goals in which one came to rest but means of ensuring repetition. Direct action had a perfect circular motion; it aimed at its own autonomous perpetuation and sovereignty. And the circle, as all students of drawing knew, was the most beautiful of forms. Thus in a sense he had returned to where he had started: terrorism was art for art's sake in the political realm."

The most important achievement of "Cannibals and Missionaries" is McCarthy's understanding of the psychology of terrorism, the perception, expressed by Henk, that terrorism is the product of despair, "the ultimate sin against the Holy Ghost." Once again, McCarthy is asking the difficult question, confronting the difficult problem. For surely, terrorism threatens us all, not only physically and politically, but morally and intellectually as well. It postulates a system of oblique correspondences, a violent disproportion between ends and means, against which we have no recourse. She comes to terms as well with our peculiar but irrefutable tendency to see human beings as replaceable, works of art unique. For the lover of formal beauty who is also a moralist, it is the most vexed of questions. I'm not sure McCarthy has anything new to say on the subject but she does not imply that she does.

Often, artists have responded to the prospect of atrocity by creating a well-crafted work of art. One thinks of Milton's "On the Late Massacre of the Piedmontese," a perfect Italian sonnet whose hundredth word is "hundredfold." In response to the truly frightful prospect of anarchic terrorism, Mary McCarthy has written one of the most shapely novels to have come out in recent years: a well-made book. It is delightful to observe her balancing, winnowing, fitting in the pieces of her plot.

The tone of "Cannibals and Missionaries" is a lively pessimism. Its difficult conclusion in that to be a human being at this time is a sad fate: even the revolutionaries have no hope for the future, and virtue is in the hands of the unremarkable, who alone remain unscathed.

Mary Gordon is the author of "Final Payments," a novel.

The Problem

The Missionaries and Cannibals problem is a classic AI puzzle that can be defined as follows: On one bank of a river are three missionaries and three cannibals. There is one boat available that can hold up to two people and that they would like to use to cross the river. If the cannibals ever outnumber the missionaries on either of the river’s banks, the missionaries will get eaten.

On one bank of a river are three missionaries and three cannibals. There is one boat available that can hold up to two people and that they would like to use to cross the river. If the cannibals ever outnumber the missionaries on either of the river’s banks, the missionaries will get eaten.How can the boat be used to safely carry all the missionaries and cannibals across the river?

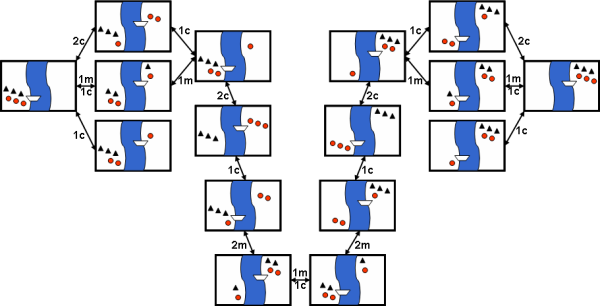

The initial state is shown to the right here, where black triangles represent missionaries and red circles represent cannibals.

Searching for a Solution

This problem can be solved by searching for a solution, which is a sequence of actions that leads from the initial state to the goal state. The goal state is effectively a mirror image of the initial state. The complete search space is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: Search-space for the Missionaries and Cannibals problem

No comments:

Post a Comment