FIRST, there are stories that engage in the highly political art of persuasion, aiming to convince a reader to take certain stands in a national or international debate - the simplest example is ''Uncle Tom's Cabin.'' But here ''The Book of Daniel'' may also be relevant insofar as, at one remove, it can affect a reader's attitude toward the cruise or Pershing missile. A second type of story deals with politicians, examples being ''The Last Hurrah,'' ''All The King's Men,'' Dos Passos' ''District of Columbia'' (whose weakness is to be biased), a good deal of Gore Vidal; I do not think this type is often found in combination with the first, since novels about politicians tend, like their heroes, to a worldly realism that would never change one's voting habits, except maybe to discourage one from voting at all. A third type ponders large political questions - essentially the nature and effects of power. The setting may be a village, a family house, a monastic community, a hospital, an air base, a hiring hall, an imaginary country such as those Gulliver visited or ''Animal Farm''; the politics may be in the play between man and Nature, man and the universe, man and God. This third type, too, being long-sighted, cannot coexist with the first, and not, I think, with the second either; a fascination with the corridors of power is always anecdotal, not reflective. Such anecdotes as appear in ''War And Peace,'' a supreme instance of Type Three, are there for illustrative purposes, to serve as examples in the ancient, rhetoricians' sense of the term. This third and noblest type may be fully represented in our fiction only by ''Moby Dick.''

|

| From the film adaptation of Moby Dick - RIP the incomparable Ray Bradbury |

What we find most often in American fiction, I believe, is the first type, though we may not recognize it or, when we do, call it propaganda, which for us is a negative word, without any of the original wholesome connotations of missionary work (de propaganda fide, spreading the faith) implicit for the Roman Church. Actually the great majority of novels in this country - maybe everywhere - have been faith- spreaders. Those are the ones we name when we are asked what books have influenced or changed us.

''

Is it an exaggeration to call ''

NATURALLY, the propaganda that works on us through fictions does not effect conversions (i.e., transformations) in ways that can necessarily be charted. If our vote on E.R.A. or a nuclear- power amendment is changed by a novel we are reading, that is only the tip of the iceberg. Probably in the 20's there were more converts made to hedonism than to any other faith, and that still may be the ''message'' of the most influential fiction of today, from Mailer to Updike and back, even when the evangel of self-expression is relayed through fears of getting cancer (Mailer) from bottling oneself up. But to go back to 30's fiction, it can be said, surely with truth, that Cesar Chavez's grape and lettuce pickers unions were helped, though with a delay of two generations, by ''The Grapes of Wrath.'' But the Joad family, ''Of Mice and Men,'' even the less accessible ''In Dubious

That American novels can be and often are political is demonstrable. There was Mailer's second novel, for instance, ''The Barbary Shore,'' laid in

In a different vein, we have had the

Most of our war novels have been pacifist in their general slant - enough to count as political. I am not sure of ''The Red Badge of Courage'' or ''A Farewell to Arms,'' but there is no doubt of ''Three Soldiers,'' ''The Naked And The Dead,'' ''From Here to Eternity,'' ''Catch- 22''(!). And the many works of

Anyone who is in the mood can continue the list. To make the point there is no need to seek to prove (as some academic recently did) that ''Moby Dick'' is an allegory of capitalism. What is interesting is that so many of the novels I have been naming have been high on the best-seller lists. The political novel in this country is certainly no fringe phenomenon. And it strikes me that we have almost more than our share of them, in comparison with England and Western Europe, just as we have had more war novels (in fact, a notable case of Type One) than our allies or adversaries, and this despite the fact that we entered both World Wars late and were never exposed to mainland attack or invasion.

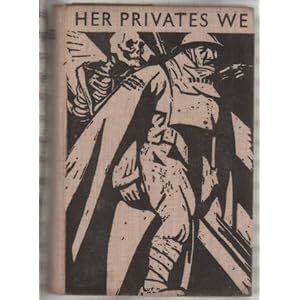

In the First War, the English had war poetry, and the Germans had ''All Quiet on The Western Front''; the French had part of Roger Martin du Gard's ''Les Thibaults,'' Henri Barbusse's ''Under Fire,'' and a film, ''La Grande Illusion.'' Out of that war, the English, as far as I remember, produced only a single novel, though that was a masterpiece, first published, in expurgated form, as ''Her Privates We'' and written in fact by an Australian, Frederic Manning. It was reissued uncut a few years ago as ''The Middle Parts of Fortune.'' A curious aspect of this pure and beautiful work, dealing with trench warfare and behind- the-lines billet life on the Somme in 1916, is the absence of politics from it, as remarkable in its way as the same absence in ''The Iliad,'' and I mean politics of any kind - there is neither glorification nor condemnation of war, still less of ''our'' side in contrast to the enemy beyond the barbed wire, and, most unusual of all, no idealization of the class of privates as opposed to the officer class that made up the basic politics of American war fiction. We will not find that neutrality in our war literature, which has a strong accusatory ring; none of our soldier-authors could have written these two sentences (from the prefatory note to ''Her Privates We,'' 1929): ''War is waged by men, not by beasts, or by gods. To call it a crime against mankind is to miss at least half its significance; it is also a punishment for a crime.''

EVEN Faulkner's ''A Fable,'' written toward the end of his life, after he received the Nobel Prize, but going back to the First War, is not dispassionate but, rather, hyperbolic about the redeeming mutiny it describes; with a silent admonitory black cross placed by Random House on the jacket, it is a pacifist parable, with funny echoes of ''A Tale of Two Cities,'' on the one hand, and of ''Hinky-dinkey parlay-voo'' (alias ''Mademoiselle from Armenteers, She Hasn't Washed in Forty Years'') on the other. Even though it is not fiction, one ought to mention E. E. Cummings's ''The Enormous Room,'' recounting his imprisonment, with Slater Brown, as a suspected spy in a French internment camp - a peak of imaginative prose writing by an American about the First War. ''A Fable,'' in fact, was Faulkner's third try at rendering some angle of that war; ''Soldier's Pay'' and ''Mosquitoes'' had to do with veterans, a political problem since Caesar's time.

No comments:

Post a Comment