By RICHARD GOODWIN

June 30, 1974

WATERGATE PORTRAITS By Mary McCarthy |

uring a recent visit to Washington, I found that a reference to Charles Colson's religious conversion guaranteed a laugh from the grimmest gathering of political sophisticates. It was sure to touch off an instant competition of Buchwald-style one-liners, tinged, nevertheless, by a slight underglow of professional appreciation for what appears to me a supreme con. I was not surprised, even though my daily journey through three newspapers - an addict's curse - had revealed in elaborate detail the precise manner and timing of this onset of grace - the slow agony of preparation, tears shed and mingled, the joy of resolution that bestows inner tranquillity before the remorseless strokes of judgment. "My President, this is why I must desert thee."

uring a recent visit to Washington, I found that a reference to Charles Colson's religious conversion guaranteed a laugh from the grimmest gathering of political sophisticates. It was sure to touch off an instant competition of Buchwald-style one-liners, tinged, nevertheless, by a slight underglow of professional appreciation for what appears to me a supreme con. I was not surprised, even though my daily journey through three newspapers - an addict's curse - had revealed in elaborate detail the precise manner and timing of this onset of grace - the slow agony of preparation, tears shed and mingled, the joy of resolution that bestows inner tranquillity before the remorseless strokes of judgment. "My President, this is why I must desert thee."

For journalism was, as is its duty, simply reporting the "facts," a category mysteriously thought to include descriptions by participants and eye-witnesses. The worldly of Washington, however, unconfined by such professional strictures were able to draw upon the knowledge, reason and experience for their own judgments. And among those who laughed were some who had edited and printed the stories.

The belief that truth is immanent in the facts, and that information can tell us what has happened or is happening, is the irredeemable flaw of journalism. In its superior wisdom, our tradition of criminal justice assumes we are more likely to approach correct knowledge by imposing news about character, probability and feeling on the external evidence and on the competing logics of analysis.

Most professional journalists reject the responsibility of the juror. They report events, and statements about events and, at times the narrowly logistical conclusions to be drawn from such facts. The avoid assertions whose truth cannot be proven, that is, most of the important truths. For example, if a White House official gives a background briefing on the status of detente, the content of that briefing is news even if the reporter believes the official to be lying.

Moreover, the Washington journalist becomes so immersed in the world of professional politics that he swiftly absorbs the fascination with tactical details and the reluctance to give public expression to harsh private judgments that pollute the air of that company town.

Nor is journalism exempt from the fear of failure - in this case the fear of error, which has displaced the desire for achievement as the fuel for American ambition. Better a lifetime without a triumph that a single Edsel. Thus, able and experienced men give us, instead of the truth, the facts which conceal the truth; they impose confusion and ambiguity on the clarity of their own knowledge.

This is why some of our best political reporting comes from outside Washington, and from writers whose profession is not politics. The line runs from Tocqueville, Bryce and Henry Adams (who did live in Washington) to Norman Mailer, Hunter Thompson and Mary McCarthy. In "Mask of State: Watergate Portraits," Mary McCarthy has collected and amplified her dispatches to the Observer of London on the Ervin Committee hearings of last summer supplemented by an analytical appraisal written last February after the hearings had ended. "In this sense," she tells us, "the book is historical."

Indeed, episode has followed episode with such swift tumult that one reads of last summer with that sense of nostalgic return ordinarily restricted to events long interred. Where were you when John Dean spilled the beans? The indignation of Weicker has already clambered to a place just beneath the tears of Joseph Welch in the pantheon of televised expiations.

Few journalists would care to publish their accounts of events so quickly superseded. But the subsequent Watergate excavations only help to confirm the perceptive usefulness of McCarthy's observations. The theme that impels these reports is character, and character is the key to Watergate.

Mary McCarthy has performed the necessary labors of journalism, having mastered the testimony and the reported facts. But she has not allowed these voluminous confusions to dilute or blunt the judgments of her novelist's sensibilities and synthesizing intelligence. Once we understand what the principal conspirators have revealed of themselves, their colleagues and then masters - not only by what they said, but through their omissions, evasions and the powerful testimony of eyes, gesture and physical presence - then we already know the truth and can predict the dismal ending. All that remains is to gather more information.

John Dean "appears free of any ideology, a strictly functional being." Since his function of the moment was to tell the truth we must believe him. John Mitchell's "mind is not supple, merely practiced in weary equivocation." In front of the committee "he sat before them stonily, the very picture of a man who had sold his silence."

While Ehrlichman came on "like a Fascist bully boy breaking up a Social Democratic picnic ... his thinking process was a massive motor response to a set of stimuli; no instant for reflection intervened. Tilting back and forth in his chair, he resembled one of those old snap-back dolls with a very low center of gravity. In this sense, he was stupid and lumpishly unaware of it."

All of them, Halderman, Ehrlichman, Mitchell, "We heard them before the Ervin Committee proclaim their guilt by open equivocation and manifest lying. Though they left us to speculate on the degree of guilt in each case, they all plainly told us they were afraid that the knowledge they carried inside them would inadvertently slip out."

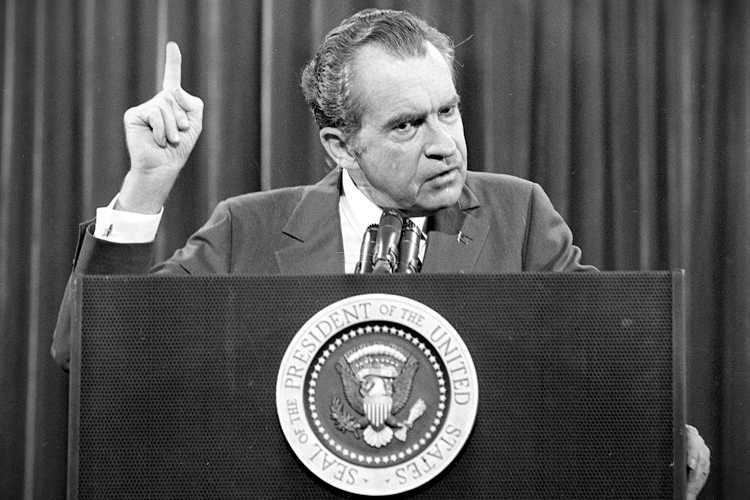

But from whom did the authority, the confirming sanction, come? Miss McCarthy carefully analyzes, and then discards, the case against each suspect, until only one remains. When did Nixon first learn about Watergate? "Ask when an arch-conspirator first heard of his conspiracy or when our wicked Creator got news of this wicked world."

Of course.

Nor has anyone experienced in national politics and knowledgeable about the operations of the Executive seriously doubted this from the beginning.

Professional journalists, most extensively James Fallows in the Washington Monthly, have faulted her for not rushing around Washington to unearth more facts; that is, for not behaving as a newspaper person should. It is a strange criticism given the established fact that most Washington reporters rarely challenge the motives or accounts of Government officials, which is why it took a couple of police reporters to break the Watergate case. Moreover, in the case of this book, such strictures are unwarranted.

The first seven chapters are on-the-spot accounts of the Ervin Committee hearings. Their factual accuracy proves that Miss McCarthy listened carefully and absorbed the substance of the testimony. When she tells us what happened her perception is fully adequate to providing an understanding of the events.

Admittedly, one whose hunger for facts, accusations and quotations is insatiable, would do better to plunge into the brain-addling flood of undigested information which is visited upon the reader of The New York Times. Mary McCarthy's aim is to interpret what is being said, and by what manner of men.

For example, Mr. Fallows criticizes Miss McCarthy's characterization of John Wilson, the lawyer for Haldeman and Ehrlichman, as a "querulous, dropsical old party with a mean city-hall mouth and a shrill, ungoverned temper recalling Rumpelstiltskin." Fallows claims that further investigation would have revealed that Mr. Wilson's shoddy and intemperate behavior was a deliberate tactic to thwart committee questioning of his clients. Perhaps. But the hearings were not a trial. By arousing public outrage and interest they prepared the necessary political support to follow. From this standpoint Mr. Wilson's "cleverness" was self-destructive foolishness, even if impelled by calculation.

Miss McCarthy's description is not simply a mistaken visceral reaction, but that aspect of the truth which is relevant to her own understanding of the purpose of the hearings. "The great service of the Ervin Committee was to show these men to the nation as they underwent questioning -- that the questioning was not always of the best, that leads were not followed up, is minor in comparison -- the Ervin Committee was not out to convict the witnesses before it -- but to give us a basis for judging them and the Administration they served. Who can deny that it did that?"

What better evidence of Mary McCarthy's journalistic skill can we ask for, than the fact that almost a year later nothing has happened which seriously contradicts her conclusions and perceptions. Despite the energetic ingenuities of all the king's lawyers and all the king's pressmen, we see them shattered now as she described them then.

It is no deprecation of Mary McCarthy's other talents to say that she is one of America's finest journalists. It is good for all of us that she has turned her powers to the inner tribulations of this country which, despite a long exile, she appears to care for very much.

No comments:

Post a Comment