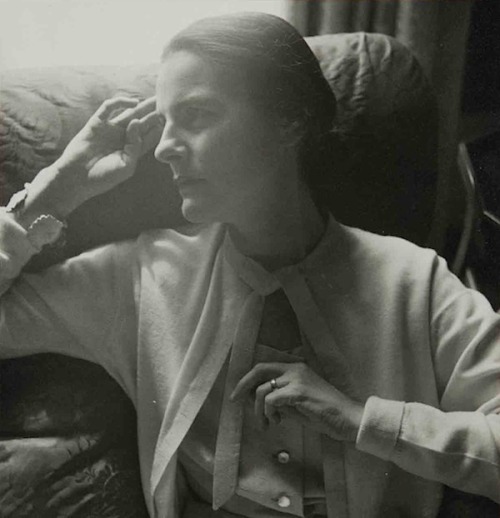

Mary McCarthy, 1955 (Cecil Beaton)

Coolheaded but Fiercely Outspoken, Mary McCarthy Never Backed Down from a Fight

She was, as the usually choleric critic John Simon once wrote, a "certifiable femme de lettres, which presupposes more than mere living by the pen. It means a multifariousness of writing skills and commitments...it means influencing public opinion through your writing." Certainly her 1963 novel, The Group, written when she was 51, changed forever the way young women from "good schools" thought about sex. Later, her nonfiction writings on McCarthyism, Vietnam and Watergate cut a wide swathe through the cant of the day.

But let us be frank: Most people remember Mary McCarthy, the prolific novelist and critic, as a writer who was never afraid of a fight.

She knocked J.D. Salinger and Tennessee Williams when they were up. She defended William Burroughs when he was down. She attacked social issues with a cool mind and a sharp tongue, never descending to sentimentality or bending to intellectual fashion. She had so many battles going that she kept a file in her Paris apartment labeled CONTROVERSY. In it, no doubt, were scorched souvenirs from her most famous fight, with another literary grande dame, Lillian Hellman.

"She is a bad writer and a dishonest writer," McCarthy said nine years ago on the Dick Cavett Show. "Every word she writes is a lie, including and and the." Hellman filed a libel suit for $2.25 million but died of a heart attack before the case could be tried. It was not the ending McCarthy had hoped for. "I didn't want her to die," she said. "I wanted her to lose in court. I wanted her around for that."

McCarthy was equally outspoken on larger issues. Cannibals and Missionaries, written in 1979, dealt with terrorism; Birds of America with the destruction of natural beauty. And if her reportage, most notably from Vietnam, was found deeply biased by some critics, well, that too was McCarthy: Morally outraged, she knew no middle ground.

Why was she like this—so ready to take up arms? Her brother Kevin McCarthy, the actor, once asked her. "For the fun of it," she replied, "or maybe a mixture of fun and principle. If nobody will speak out on a subject, I will."

Perhaps the adversity that came so early to Mary McCarthy helps explain why readiness to fight was her natural state. Orphaned at 6, when her parents died in the flu epidemic of 1918, McCarthy was left with her three brothers in the care of a brutally strict great-aunt and great-uncle in Minneapolis. She was beaten when she misbehaved; she was also beaten when she won a prize in an essay contest. "I had no need to ask why," she wrote in her memoir How I Grew. "It was to keep me from getting stuck-up."

She was rescued, after five years, by her maternal grandfather, who sent Mary to a fine boarding school and then on to Vassar, where she quickly made her mark as a writer.

Hers was not a traditional Catholic girlhood. She shaved off half her eyebrows in prep school to cultivate an original look and lost her virginity at 14, in the front seat of a Marmon roadster. After college she married actor Harold Johnsrud and began publishing reviews in the Nation and Partisan Review.

Detractors credited her early success to a love affair with review editor Philip Rahv, and it was true that McCarthy seems to have taken a utilitarian view of men: Rahv was soon discarded for critic Edmund Wilson, 17 years her senior, whom she married in 1938 after divorcing Johnsrud. It was Wilson who encouraged McCarthy to write fiction, pushing her into a room and forbidding her to come out until she finished a piece. It is a tribute to McCarthy's consistency of character that she proceeded to write an unflattering account of her husband. When he saw the final product, McCarthy reported, he was quite furious. "I showed it to you before," said Mary. "But you improved it," said Wilson.

Wilson and McCarthy had one son, Reuel Kimball, now a professor of Slavic languages, and divorced in 1946. Within a month she married writer and teacher Bowden Broadwater. Already she was notorious for sexually frank fiction like The Man in the Brooks Brothers Shirt, which describes a young woman having sex with a stranger on a train. "There was the shock value," recalls novelist Alice Adams. "The effect was liberation." Yet McCarthy was no feminist. Asked in 1984 whether the women's movement had produced any distinguished writing, she replied, bluntly, "No." But she cast the same cold eye on her own work. "I don't particularly like The Group," she said in 1979. "I think it's a bit coarse."

In recent years McCarthy and her fourth husband, James West, a former State Department official, divided their time between Paris and Castine, Maine. Despite her advancing cancer, McCarthy, at the time of her death, was said to be working as intensely as ever. Reporters who visited her used the word journalists employ when describing a personage of a certain age: They said McCarthy had mellowed.

Not likely.

No comments:

Post a Comment