inability to speak was closely connected with an inability to think, namely, to think from the standpoint of somebody else. No communication was possible with him, not because he lied but because he was surrounded by the most reliable of all safeguards against the words and the presence of others, and hence against reality as such . . . [It was] proof against reason and argument and information and insight of any kind (see Eichmann in Jerusalem, chapters 3 and 5).Having encountered such a man, Arendt saw that the banality of evil is potentially far greater in extent--indeed limitless--than the growth of evil from a "root." A root can be uprooted, which is what she meant to do when she spoke of "destroying" totalitarianism, but the evil perpetrated by an Eichmann can spread over the face of the earth like a "fungus" precisely because it has no root. Furthermore, the case of Eichmann led Arendt to see that at least one evildoer was not "corruptible." Having overcome or in his case forgotten any inclination he may have had to halt or hinder the organization and transportation of millions of innocent Jews to their deaths, Eichmann boasted that he had done his duty to the end! Unlike Himmler, his ultimate superior in the chain of command and a chief architect of the "final solution," Eichmann never attempted to "negotiate" with the enemy when it became clear that the Nazi cause was lost. He declared, on the contrary, "that he had lived his whole life . . . according to a Kantian definition of duty," (see Eichmann in Jerusalem, chapter 8) and Arendt noted that "to the surprise of everybody, Eichmann came up with an approximately correct definition of [Kant's] categorical imperative," though he had "distorted" it in practice. She admitted, moreover, "that Eichmann's distortion agrees with what he himself called the version of Kant 'for the household use of the little man,'" the identification of one's will with "the source" of law, which for Eichmann was the will of the Führer.

Just as you supported and carried out a policy of not wanting to share the earth with the Jewish people and the people of a number of other nations--as though you and your superiors had any right to determine who should and who should not inhabit the world--we find that no one, that is, no member of the human race, can be expected to share the world with you. This is the reason, and the only reason, you must hang (see Eichmann in Jerusalem, "Epilogue" -- part one and part two").

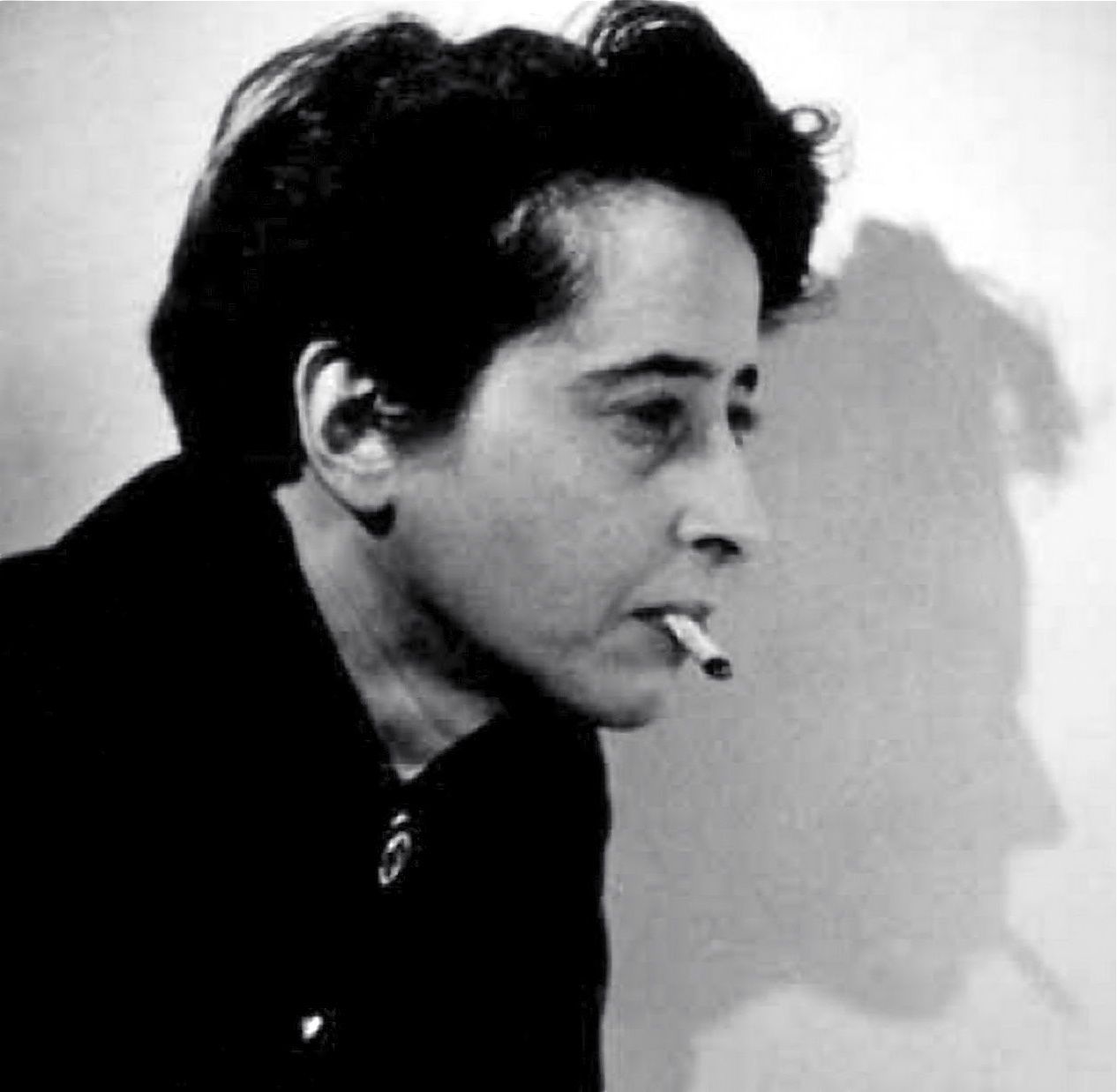

Hannah Arendt and Mary McCarthy, 1960s. Courtesy of the Hannah Arendt Trust. |

Mary McCarthy with Hannah Arendt, Aberdeen, Scotland, ca. 1974. Courtesy of the Hannah Arendt Trust. |

February 19, 1995

The Group of Two By LORE SEGAL

BETWEEN FRIENDS

The Correspondence of Hannah Arendt and Mary McCarthy, 1949-1975.Edited by Carol Brightman.

t was at a New York party in 1945 that Mary McCarthy, an American, a Roman Catholic, a novelist and a critic, offended the philosopher Hannah Arendt, a German-born Jew. Unable, one imagines, to refrain from an opportunity for wit, McCarthy said she felt sorry for Hitler, who wanted even his victims to love him. Arendt asked how such a thing could be said to her, a Hitler victim who had been in a concentration camp.

In her introduction to "Between Friends: The Correspondence of Hannah Arendt and Mary McCarthy, 1949-1975," the editor, Carol Brightman, reports that it was Arendt who put an end to the following three years' chill between the two women, admitting to McCarthy that the French camp where she had been interned was not a concentration camp. "We think so much alike," Arendt said to McCarthy, offering an intense friendship that lasted until Arendt's death and is documented in their 26-year correspondence.

Their letters tend to open like everybody else's, with puzzled regret at not having written sooner. Both were extraordinarily active: they thought, wrote and published; they taught, lectured and traveled; they leaped into controversies. Both became famous, and fame can be a burden. In 1963, after publication of her novel "The Group," McCarthy wrote, "Success seems to take so much of your time, you are devoured by it."

In their letters they ranged widely. They gossiped, laughed at their friends and worried about them. They talked politics, exchanged philosophical ideas, celebrated and criticized each other's work. They write "I am really homesick for you," and they long "just to see you and talk." Before they close each remembers to send affectionate messages to the other's husband. In 1949, at the beginning of the correspondence, McCarthy had divorced Edmund Wilson (that "old woman") and married Bowden Broadwater ("just two people playing house like congenial children"). McCarthy communicated her intimate adventures to her friend. She asked for Arendt's discretion when she confided in her about a hapless London affair and about the theologian Paul Tillich's attempt to seduce her on a trans-Atlantic crossing. In 1960 Arendt was privy to McCarthy's discovery of more and more charms and virtues in her new love, the American diplomat James West, who was to be her fourth and final husband. "He has a kind of exquisite tenderness, toward things as well as persons," McCarthy wrote from Warsaw; "the ordinary Poles . . . all love him." She suspected her friends, yes, even dearest Hannah, of "condoning" those two dastardly soon-to-be-exes -- her current husband, Broadwater, and West's wife -- who were not letting themselves be shed quietly. In a characteristic letter -- clear, firm, not unsympathetic -- Arendt explained that she was not about to turn against Broadwater while his life was in ruins and reminded McCarthy that she had once trusted him enough to marry him. It is the only time in their correspondence when McCarthy could not hear what her friend was saying.

Arendt thought of herself as reticent. In 1970, after her Berlin-born husband, Heinrich Blucher, died of a heart attack, she wrote, "I don't think I told you that for 10 long years I had been constantly afraid that just such a sudden death would happen." McCarthy replied that she had known of Arendt's fear. It was Arendt who was unaware of having communicated her continual fright, which she said "frequently bordered on real panic."

What sort of friendship was it between these two women with such different pasts and temperaments?

It's not that they "think so much alike," but that they did what Hannah Arendt called "this thinking-business" for and with each other. There are letters that read like little essays by Montaigne. Of Truth: Arendt said it was not "the end of a thought-process" but "the condition for the possibility of thinking." Of Equality: McCarthy wrote that it was a worm "eating away . . . the 'class distinctions' between the sane and the insane, the beautiful and the ugly." "Let us talk about the equality business; most interesting," replied Arendt, adding that "constant comparing is really the quintessence of vulgarity."

"Taste," Arendt wrote on another occasion, "is a principle of 'organization,' " of "who in the world belongs together" and how "we recognize each other." Hannah Arendt and Mary McCarthy recognized and belonged with each other. Both responded to the political moment; they were on the same side. We read their letters, and like the stage manager in Thornton Wilder's "Our Town," we revisit events whose outcomes we suffered years ago. McCarthy was early and urgent in wanting to do something about Senator Joseph R. McCarthy. The next situation they could do nothing about was the 1952 Presidential election. McCarthy didn't know what to think of Adlai Stevenson, but wrote: "My breath is bated to see what he would do in office. . . . The wit is not very good, but the sarcasms are alive." She thought Richard Nixon's success as a Vice-Presidential candidate "would mean that mass society is a reality, which nobody here . . . really has ever believed except in talk." In 1960 McCarthy quipped that Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet leader, was "not a human being but a figure in a serial comic strip . . . an outline drawing." The assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 "is going to be one of those litmus-paper issues or goat-and-sheep dividers, like the Moscow Trials and Pasternak and your 'Eichmann.' " In 1965 Arendt summarized a scenario she had read about "a neat little nightmare" of China declaring war on the United States and then overwhelming us by surrendering. And then Vietnam: though "hamstrung" by her husband's Foreign Service career, McCarthy again felt she must do something, and in 1968 she visited Hanoi.

They worried about their friends: when Robert Lowell had another breakdown, McCarthy wrote, "Cal is in poor shape again; it must be the most monotonous fate for him." When the poet W. H. Auden died in 1973, Arendt sadly remembered refusing "to take care of him when he came and asked for shelter." He had come, a month after Heinrich's death, wanting her to marry him.

Husbands, lovers, friends, acquaintanceships -- their salon spread across the Western world. There are philosophers: Karl Jaspers, Martin Heidegger, Isaiah Berlin; French intellectuals, including Jean-Paul Sartre and Nathalie Sarraute; in Italy, the writers Alberto Moravia and Ignazio Silone and the American connoisseur Bernard Berenson. Arendt disliked Vladimir Nabokov: "He thinks of himself in terms of 'more intelligent than,' " a vulgarity she said she was allergic to because "I know it so well, know so many people cursed with it." Arendt and McCarthy had the same taste in vulgarity. The very laws of probability conspired to keep them from contact with regular people, which was just as well for the regular people. As a guest at the Villa Serbelloni, the Rockefeller Foundation's Italian retreat, Hannah Arendt found herself amid "scholars, or rather professors, from all countries . . . with their wives, some of them are plain nuts, others play the piano or type busily the non-masterworks of their husbands."

The friends read and admired each other's work. "The sensation of being honored doesn't diminish with familiarity," McCarthy wrote in answer to a fan letter from Arendt. They honored each other with criticism. McCarthy pointed out some "barbarisms" in Arendt's English usage and chided Arendt's translators, "whose language, far from achieving precision, creates a blur."

In her letters to Arendt, McCarthy might acknowledge certain weaknesses in herself as novelist, but against the critical world the two friends manned the trenches together for each other. Arendt on a negativereview of McCarthy's novel "Birds of America": "The old malice. . . . Also of course sheer stupidity." McCarthy on editorial politics: a negative review of Arendt's "Human Condition" "was certainly commissioned, the way you commission a murder from a gangster."

Their good friend Elizabeth Hardwick's anonymous spoof of "The Group," published in The New York Review of Books as "The Gang," and Norman Mailer's pan of the same novel have become literary footnotes. But the simultaneous furor over Hannah Arendt's "Eichmann in Jerusalem" -- particularly its subtitle, "A Report on the Banality of Evil," and the issue of Jewish cooperation with the Nazis -- is likely to revive with the publication of these letters. We Jews continue to feel the Holocaust as a wound; therefore we prescribe the manner in which it can be handled. At that party in 1945, Mary McCarthy handled it badly and Arendt cried out. In 1963 Arendt attended the Eichmann trial, and followed the facts, as she saw them, where they led her. The book raised a cry of pain that never quite subsided.

In his response in Partisan Review, Lionel Abel wanted to differentiate between Arendt's "esthetic" and his own (superior) "moral" judgment. But isn't moral judgment, too, a matter of "taste," that is to say of the "principle of organization" by which we understand innocence and evil? The litmus test divides those who need their victims to be driven-snow white from those who see them in every shade. There are those to whom evil is more terrible when it is absolute, an idea, inhuman, and those of us who fear that it is human indeed, ubiquitous, available at all times for the totalitarian idea. Sympathetic Mary McCarthy, with only one Jewish grandmother, rushed in, said everything all wrong, and apologized to her friend for making more trouble.

Jane Austen understood such friendship between women: "There was not a creature in the world to whom she spoke with such unreserve . . . with such conviction of being listened to and understood, of being always interesting and always intelligible." And "the very sight of Mrs. Weston, her smile, her touch, her voice was grateful to Emma."

Hannah Arendt, German-born, a Jew, a Hitler victim, also understood it, and summed it up for the American Catholic, Mary McCarthy: "Your cards and letters -- so dear and then also so immensely sensible, just the day-to-day continuity of life and friendship."

Lore Segal's first novel, "Other People's Houses," and her most recent, "Her First American," have been reissued in paperback.

During its first few years, Hitler's rise to power appeared to the Zionists chiefly as 'the decisive defeat of assimilationism'. Hence, the Zionists could, for a time, at least, engage in a certain amount of non-criminal cooperation with the Nazi authorities; the Zionists too believed that 'dissimilation', combined with the emigration to Palestine of Jewish youngsters and, they hoped, Jewish capitalists, could be a 'mutually fair solution'. At the time, many German officials held this opinion, and this kind of talk seems to have been quite common up to the end. A letter from a survivor of Theresienstadt, a German Jew, relates that all leading positions in the Nazi-appointed "Reichsvereiningung" were held by Zionists (whereas the authentic Jewish "Reichsvereiningung" had been composed of both Zionists and non-Zionists), because Zionists, according to the Nazis, were the 'decent' Jews since they too thought in 'national terms'. To be sure, no prominent Nazi ever spoke publicly in this vein; from beginning to end, Nazi propaganda was fiercely, unequivocally, uncompromisingly anti-Semitic, and eventually nothing counted but what people who were still without experience in the mysteries of totalitarian government dismissed as 'mere propaganda'. There existed in those first years a mutually highly satisfactory agreement between the Nazi authorities and the Jewish Agency for Palestine - a 'Ha'avara', or Transfer Agreement, which provided that an emigrant to Palestine could transfer his money there in German goods and exchange them for pounds upon arrival. It was soon the only legal way for a Jew to take his money with him (the alternative then being the establishment of a blocked account, which could be liquidated abroad only at a loss of between fifty and ninety-five per cent). The result was that in the thirties, when American Jewry took great pains to organize a boycott of German merchandise, Palestine, of all places, was swamped with all kinds of goods 'made in Germany'.

"Of Greater importance for Eichmann were the emissaries from Palestine, who would approach the Gestapo and the S.S. on their own initiative, without taking orders from either the German Zionists or the Jewish Agency for Palestine. They came in order to enlist the help for the illegal immigration of Jews into British-ruled Palestine, and both the Gestapo and the S.S: were helpful. They negotiated with Eichmann in Vienna, and they reported that he was 'polite', 'not the shouting type', and that he even provided them with farms and facilities for setting up vocational training camps for prospective immigrants. ('On one occasion, he expelled a group of nuns from a convent to provide a training farm for young Jews' and on another 'a special train was made available and Nazi officials accompanied' a group of emigrants, ostensibly headed for Zionist training farms in Yugoslavia, to see them safely across the border). According to the story told by Jon and David Kimche, with 'the full and generous cooperation of all the chief actors' (The Secret Roads: The 'Illegal' Migration of a People, 1938-1948, London, 1954), these Jews from Palestine spoke a language not totally different from that of Eichmann. They had been sent to Europe by the communal settlements in Palestine, and they were not interested in rescue operations: 'That was not their job'. They wanted to select 'suitable material', and their chief enemy, prior to the extermination program, was not those who made life impossible for Jews in the old countries, Germany or Austria, but those who barred access to the new homeland: that enemy was definitely Britain, not Germany. Indeed, they were in a position to deal with the Nazi authorities on a footing amounting to equality, which native Jews were not, since they enjoyed the protection of the mandatory power; they were probably among the first Jews to talk openly about mutual interests and were certainly the first to be given permission 'to pick young Jewish pioneers' from among the Jews in the concentration camps. Of course, they were unaware of the sinister implications of this deal, which still lay in the future; but they too somehow believed that if it was a question of selecting Jews for survival, the Jews should do the selecting themselves. It was this fundamental error in judgement that eventually led to a situation in which the non-selected majority of Jews inevitably found themselves confronted with two enemies - the Nazi authorities and the Jewish authorities".

(pp. 59-61)

To a Jew this role of the Jewish leaders in the destruction of their own people is undoubtedly the darkest chapter of the whole dark story. It had been known about before, but it has now been exposed for the first time in all its pathetic and sordid detail by Raul Hilberg, whose standard work *The Destruction of the European Jews* I mentioned before. In the matter of cooperation, there was no distinction between the highly assimilated Jewish communities of Central and Western Europe and the Yiddish-speaking masses of the East. In Amsterdam as in Warsaw, in Berlin as in Budapest, Jewish officials could be trusted to compile the lists of persons and of their property, to secure money from the deportees to defray the expenses of their deportation and extermination, to keep track of vacated apartments, to supply police forces to help seize Jews and get them on trains, until, as a last gesture, they handed over the assets of the Jewish community in good order for final confiscation. They distributed the Yellow Star badges, and sometimes, as in Warsaw, 'the sale of the armbands of cloth and fancy plastic armbands which were washable'. In the Nazi-inspired, but not Nazi-dictated, manifestos they issued, we still can sense how they enjoyed their new power - 'The Central Jewish Council has been granted the right of absolute disposal over all Jewish spiritual and material wealth and over all Jewish manpower', as the first announcement of the Budapest Council phrased it. We know how the Jewish officials felt when they became instruments of murder - like captains 'whose ships were about to sink and who succeeded in bringing them safe to port by casting overboard a great part of their precious cargo'; like saviors who 'with a hundred victims save a thousand people, with a thousand ten thousand'. The truth was even more gruesome. Dr. Kastner, in Hungary, for instance, saved exactly 1,684 people with approximately 476,000 victims. In order not to leave the selection to 'blind fate', 'truly holy principles' were needed 'as the guiding force of the weak human hand which puts down on paper the name of the unknown person and with this decides his life or death'. And whom did these 'holy principles' single out for salvation? Those 'who had worked all their lives for the 'zibur' (community)' - i.e. the functionaries - and the 'most prominent Jews', as Kastner says in his report.

"No one bothered to swear the Jewish officials to secrecy; they were voluntary 'bearers of secrets', either in order to assure quiet and prevent panic, as in Dr. Kastner's case, or out of 'humane' considerations, such as that 'living in the expectation of death by gassing would only be the harder', as in the case of Dr. Leo Baeck, former Chief Rabbi of Berlin. During the Eichmann trial, one witness pointed out the unfortunate consequences of this kind of 'humanity' - people volunteered for deportation from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz and denounced those who tried to tell them the truth as being 'not sane'. We know the physiognomies of the Jewish leaders during the Nazi period very well: they ranged all the way from Chaim Rumkowski, eldest of the Jews in Lodz, called Chaim I, who issued currency notes bearing his signature and postage stamps engraved with his portrait, and who rode around in a broken-down horse-drawn carriage; through Leo Baeck, scholarly, mild-mannered, highly educated, who believed Jewish policemen would be 'more gentle and helpful' and would 'make the ordeal easier' (whereas in fact they were, of course, more brutal and less corruptible, since so much more was at stake for them); to, finally, a Jew who committed suicide - like Adam Czerniakow, chairman of the Warsaw Jewish Council, who was not a rabbi but an unbeliever, a Polish-speaking Jewish engineer, but who must still have remembered the rabbinical saying: 'Let them kill you, but don't cross the line'." (pp. 117-119)

But the whole truth was that there existed Jewish community organizations and Jewish party and welfare organizations on both the local and the international level. Wherever Jews lived, there were recognized Jewish leaders and this leadership, almost without exception, cooperated in one way or another, for one reason or another, with the Nazis. The whole truth was that if the Jewish people had really been unorganized and leaderless, there would have been chaos and plenty of misery but the total number of victims would hardly have been between four and half and six million people". (p.125).

That Europe's Jewish organisations in the main, played a 'disastrous role' by cooperating with the Nazi extermination machine. As a result the Jews, themselves, bear a large share of the blame" (emphasis added) (ibid.)

In other words, as everybody soon knew and repeated, my 'thesis' was that the Jews had murdered themselves

The author would have you believe that Eichmann really wasn't a Nazi, that the Gestapo aided Jews, that Eichmann actually was unaware of Hitler's evil plans...

No one will doubt the effectiveness of modern image-making and no one acquainted with Jewish organisations and their countless channels of communication outside their immediate range will underestimate their possibilities in influencing public opinion. For greater than their direct power of control is the voluntary outside help upon which they can draw from Jews who, though they may not be at all interested in Jewish affairs, will flock home, as it were, out of age-old fears (no longer justified, let us hope, but still very much alive) when their people or its leaders are criticized. What I had done according to their lights was the crime of crimes. I had told 'the truth in a hostile environment,' as an Israeli official told me, and what the A.D.C. and all the other organizations did was to hoist the danger signal..." (p.275).

Or was it? After all, the denunciation of book and author, with which they achieved great, though by no means total, success, was not their goal. It was only the means with which to prevent the discussion of an issue 'which may plague Jews for years to come'. And as far as this goal was concerned, they achieved the precise opposite. If they had left well enough alone, this issue, which I had touched upon only marginally, would not have been trumpeted all over the world. In their efforts to prevent people from reading what I had written, or, in case such misfortune had already happened, to provide the necessary reading glasses, they blew it up out of all proportion, not only with reference to my book but with reference to what had actually happened. They forgot that they were mass organisations, using all the means of mass communication, so that every issue they touched at all, pro or contra, was liable to attract the attention of masses whom they then no longer could control. So what happened after a while in these meaningless and mindless debates was that people began to think that all the nonsense the image-makers had made me say was the actual historical truth. Thus, with the unerring precision with which a bicyclist on his first ride will collide with the obstacle he is most afraid of, Mr. Robinson's formidable supporters have put their whole power at the service of propagating what they were most anxious to avoid. So that now, as a result of their folly, literally everybody feels the need for a 'major work' on Jewish conduct in the face of catastrophe (ibid.)

|

| Margarethe von Trotta |

Joe, in real life a diabetic businessman from Belmont, Massachusetts, had spent thirty years beating his competitors to the jump. Joe’s intentions toward Utopia were already formidable: honoring its principles of equality and fraternity, he was nevertheless determined to get more out of it than anybody else … He intended to paint more, think more, and feel more than his co-colonists … He would not have been in earnest about the higher life if he had failed to think of it in terms of the speed-up.Then, for (sadly) comic relief, we have Katy and Preston, who, married a bare two years and ardently of the purist party, are mainly involved in strategizing their marital misery. Whenever they have an argument Katy instantly goes on an emotional jag that Preston despises and has never known how to escape; but now he, “no doubt about it, was taking advantage of the Utopian brotherhood to shut her out from himself.” Utopia was giving him “a privacy he had sought in vain during [their] two years of marriage.” Katy, in turn, was discovering that “the privacy to make a scene was something she would miss in Utopia … [N]ow, surrounded by these watchers, she felt deprived of a basic right … [to] behave badly if necessary, until [Preston] responded to her grief.”

A phase of the colony had ended, everyone privately conceded.… The distaste felt by some … was so acute that they questioned the immediate validity of staying on in a colony where such a thing could take place. The fault, in their view, lay with no single person, but with the middle-class composition of the colony, which, feeling itself imperiled, had acted instinctively, as an organism, to extrude the riffraff from its midst.The mockery ends in self-mockery as one of the Utopians observes, “Nice people like these are always all right, unless you take them off guard.”