Wednesday 23 October 2013

Sunday 20 October 2013

Hanoi/Paris 1968: MM on the Front Lines

North Vietnam: The Countryside

“Go out into the field,” American officials last year, in blustery hectoring tones, were telling newcomers to Saigon, meaning get close to the fighting if you want to “connect” with the war. In North Vietnam, officials do not stipulate a tour of the combat zones as a condition for climbing aboard, “turning on,” or, as they would express it, “participating in the struggle of the Vietnamese people.” Indeed, if I had wanted to be taken to the 17th parallel, they would surely have said no: too long and dangerous a trip for a fleeting guest of the Peace Committee. And too uncertain, given the uneven pace of travel by night, in convoy, to plan ahead for suitable lodging, meals, entertainment. A reporter on the road can trust to pot-luck and his interpreter, but for guests hospitality requires that everything be arranged in advance, on the province and district, even the hamlet level, with the local delegates and representatives—stage-managed, a hostile critic would say, though, if so, why the distinction between guests and correspondents? Anyway, that is how it is, and I do not feel it as a deprivation that I failed to see the front lines. The meaning of a war, if it has one, ought to be discernible in the rear, where the values being defended are situated; at the front, war itself appears senseless, a confused butchery that only the gods can understand; at least that is how Homer and Tolstoy saw the picture, in close-up, though the North Vietnamese film studios certainly would not agree.

Nevertheless, it was a good idea—and encouraged by Hanoi officials—to get out of Hanoi and go, not into the field but into the fields. In the countryside, you see the lyrical aspect of the struggle, i.e., its revolutionary content. All revolutions have their lyrical phase (Castro with his men in an open boat embarking on the high seas), often confined to the overture, the first glorious days. This lyricism, which is pulsing in Paris today as I write, the red and black flags flying on the Sorbonne, where the revolting students have proclaimed a States General, is always tuned to a sudden hope of transformation—something everybody would like to do privately, be reborn, although most shrink from the baptism of fire entailed. Here in France the purifying revolution, which may be only a rebellion, is still in the stage of hymns to liberty, socialist oratory, mass chanting, while the majority looks on with a mixture of curiosity and tolerance. But in rural North Vietnam, under the stimulus of the US bombing, a vast metamorphosis, or, as the French students would say, re-structuring, is taking place not as a figure of speech but literally. Mountains, up to now, have not been moved, but deep caverns in them have been transformed into factories. Universities, schools, hospitals, whole towns have been picked up and transferred from their former sites, dispersed by stealth into the fields; streams have changed their courses …

New York

June 13, 1968

Dearest Mary

I wanted to write yesterday just after reading the third instalment of the Hanoi book. I rarely saw Heinrich so enthusiastic. I love it enormously. This still and beautiful pastoral of yours has the effect of showing the whole monstrosity of our enterprise in a harsher light than any denunciation or description of horror could. It is beautifully written, one of the very finest, most marvellous things you have ever done...

I miss you. There are many things - also political things - which I wished we could talk about...Things, of course, look pretty bleak. Do you happen to know Dani Cohn- Benditt (sic)? He happens to be the son of very close friends of ours and I wish I knew a way of contacting him. I know him, though not well...I just want him to know that the old Paris friends...are very willing to help if he needs it.

Much, much love

Hannah

Die Welt: What did Hannah Arendt mean to you, when you were still a real, radical leftist 68er?

Daniel Cohn-Bendit: That's complicated, because she was a friend of my parents. I knew her and was aware of her theses as a child. After emigrating in 1934, she belonged to a group of intellectuals in Paris along with my parents, Walter Benjamin and Hannah Arendt's husband Heinrich Blücher. My father and Blücher were interned together at the beginning of the war, and that resulted in a deep friendship. But you make a point in your question: Hannah Arendt was not the most influential thinker for me at that time.

Daniel Cohn-Bendit: That's complicated, because she was a friend of my parents. I knew her and was aware of her theses as a child. After emigrating in 1934, she belonged to a group of intellectuals in Paris along with my parents, Walter Benjamin and Hannah Arendt's husband Heinrich Blücher. My father and Blücher were interned together at the beginning of the war, and that resulted in a deep friendship. But you make a point in your question: Hannah Arendt was not the most influential thinker for me at that time.

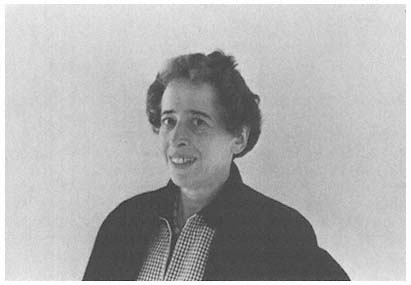

Hannah Arendt 1941. Foto: Fred Stein

Hannah Arendt 1941. Foto: Fred SteinWhen she held a laudatio for Karl Jaspers in 1958, when he received the Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels. My father had just died and she visited my mother. The second time I saw her was at the Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt. I was there with my school class – and she happened to be there too.

When did you begin to get interested in Hannah Arendt's work?

In the 1970s, as the discussions about totalitarianism became more and more pressing. I was a leftist anti-communist and when I came to Germany in 1968, I was perplexed by the reluctance to compare communism with national socialism, which was rooted in German history.

Did your referring to Hannah Arendt's "The Origins of Totalitarianism" lead to conflicts with your colleagues?

There was conflict from the outset, because when I was expelled from France in 1968, I was absolutely certain that, despite my revolutionary convictions, I would prefer to live in West Germany than in the GDR. I saw in France and the GDR bourgeois societies – that's what we called them back then – that needed reform but not totalitarian systems.

Hannah Arendt wrote to Daniel Cohn-Bendit in June, 1968 that "..your parents would be very pleased with you if they were alive now."

McCarthy on the Front Line 1968 : La Lutte Continuee

Mary McCarthy returned from Hanoi to Paris in May 1968 - from the front-line of anti-imperialist war resistance in SE Asia to the front-line of anti-capitalist revolution in NW Europe : context below by Pierre Lambert

Revolution in France:

betrayed but not defeated

Pierre Boussel Lambert: born Paris 9 June 1920, died Paris 16 January 2008

This analysis was originally published in the immediate aftermath of the May/June events

in the journal Fourth International, August 1968 edition

THE GREAT STRIKE movement of May and June 1968 which brought the French working class within sight of power has enormous political significance and requires careful analysis and study. All the problems raised by the revolution in advanced capitalist countries were suddenly presented in living form. By their action in downing tools together and occupying their places of work ten million workers demonstrated their strength and shook the bourgeois state to its foundations. For the space of two weeks France stood on the brink of a revolution which, given leadership, could have carried the working class to power with little bloodshed. The paralysis of the

economy was complete; the state power was in eclipse and the bourgeoisie was stricken

with panic and confusion. What many had believed to be impossible, a revolutionary

situation in an advanced country, was now plainly in existence. At one point bourgeois

rule depended upon nothing more than a few tens of thousands of riot police and an

uncertain army largely composed of conscript soldiers who would be asked to fire on

their fathers and brothers.

And yet, almost as rapidly as the crisis broke and the question of workers’ power was

posed, the ruling class resumed its poise; de Gaulle re-asserted his command, the strikes were

brought to an end and elections confirmed the Gaullist victory by a substantial majority.

The change in the situation was so rapid and so complete that the question of how near

France actually was to revolution in May will undoubtedly become a perennial subject of

historical controversy. In retrospect many of those who, at the height of the battle in May,

foresaw a defeat for the bourgeoisie have already revised their opinion and now claim that

the issue was never in doubt. True, for a final historical judgement, many of the necessary

elements are lacking. In particular it will be a long time before we know what was going

on in the inner councils of the Gaullist government. Did it, before de Gaulle’s broadcast

of May 30, at some point decide that the game was up, as stories that the Ministries were

burning confidential papers seem to suggest? What was the relationship between the

government and the leadership of the CGT and the Communist Party and was a guarantee

actually given (or even required) from the Soviet Ambassador that there was no intention

of turning France into a ‘People’s Democracy’? In the event of a workers’ revolution would

the army leaders have plunged the country into civil war?

In fact we do not have to answer these

questions in order to be able to raise, and

in part answer, the more immediate and

vital ones raised by these events.

In the first place the lie has been

given to the myth that the working class

in the advanced countries has become

an inert and demoralized force. In

and displayed their power. It is true that

the signal was given by the students, but

the situation did not have revolutionary

implications until the workers occupied

the factories and began to make their

own demands. It is true, also, that in

form these demands were mainly of an

economic nature; but, by their extent,

their manner of presentation and the

context in which they were made they also represented a direct challenge to the ruling

class and its state.

More important still was the fact that the level of this challenge was directly related

to the ability of the Communist and reformist parties and the trade union bureaucracies

to control the strike movement and confine it to what were called ‘professional’ demands.

After the massive demonstrations of May 13, in which the workers expressed their

solidarity with the students in struggle against the Gaullist regime, the ‘left’ parties and

unions, and especially the Stalinists, hoped that these energies could be channelled back

into the usual humdrum forms and that the situation would be restored to normal. It

was the action of the workers at Sud-Aviation and the Renault plants in occupying their

factories which set in train the mass strikes which the CGT and the other unions had

neither prepared for, called nor desired.

It was as though all the locks which the bureaucracies had placed on the combativity

of the workers for many years were suddenly blown off. Following the example of the

students, the young workers in particular demanded action to protect wage packets

which were shrinking under the pressure of rising prices and against intolerable working

conditions and lack of a real future. Plants which had not had strikes for three decades

came out solidly, sections of workers reputedly the most docile and least class-conscious

in department stores, offices and banks demanded to join the strike. All over the country

universities, schools and public buildings were occupied. Over many the red flag was

substituted for the tricolour. The gates were locked, pickets and strike committees were

set up. All the major plants, except in a few

backward areas, from government arsenals to

the big motor works, were in the hands of their

workers. Electricity and other services only

functioned by permission of the workers.

Yet a general strike was never called by

the CGT or any other trade union body.

L’Humanité never issued such a call nor, in

its front page headlines, did it ever provide

slogans or a lead for the strikers. The

Communist Party, and its members in the

leadership of the CGT, struggled might and

main to limit the scope of the strike to the basic

economic demands which, however heavy

for the capitalists to meet, still accepted the

framework of bourgeois property relations.

There was no national direction of the strike and it was everywhere the policy of the CP

to prevent a link-up between the strike committees in the separate enterprises. The CGT

negotiated with the government, as did the other national confederations (CFTD, Force

Ouvriere, CGC), and as soon as possible went back to the enterprises with the terms

which had been provisionally agreed upon. Thus a key role was played by the refusal of

the Renault workers to accept the model agreement brought back from his meeting with

the government by Georges Seguy, the general secretary of the CGT on May 27. This

ensured that the strike would continue and that more then ever, in the next few crucial

days, the question of power would be posed.

At this point it is clear that the Communist Party set itself solidly against any

movement to take power. This is borne out by the tone of the statement of the Central

Committee dated May 27. In substance this declared opposition to those who claimed

that the situation was ‘revolutionary’; called on followers of the CP not to join in the

student demonstration called for that day; and stated its aim to be ‘a government of

democratic union’ with the Left Federation – at that time in almost complete eclipse

– the dissolution of the National Assembly and the holding of new elections.

That was on May 27 when the disarray of the government and the demoralization of

the bourgeoisie were still apparent. On May 30, in a radio broadcast, de Gaulle signalled

the turn of the tide for the bourgeoisie, echoing the call of the Communist Party for

dissolution of the National Assembly and new elections and promising stern measures.

Immense relief of the bourgeoisie and a massive Gaullist procession in Paris. Reaction of

the CP: relief and satisfaction (the Party had apparently wanted elections all along!).

In the following days and weeks the Stalinist bureaucracy fought day and night to settle

Return to normal...2

revolution

the strikes and hand back the factories to their lawful owners. At the same time it settled

down to the electoral campaign, carefully distinguishing itself from the ‘revolutionaries’

of May. The Communist Party was, as Waldeck-Rochet put it, ‘a revolutionary party in

the best sense of the term’, that is to say, a party which ensured that a revolution did not

take place.

Then and since Stalinist propagandists, and those who cover up for them, have

been working hard to prove that the situation in France in May was not revolutionary

and to discredit all those who claim it was. For all the conditions to be present for a

revolutionary situation there has of course to be a revolutionary party able to heighten

the consciousness of the working class and lead it to power. As the principal political

party of the working class, and as the leader of the largest trade union confederation,

Stalinism did everything it could to confine the strikes to material objectives consistent

with the preservation of capitalism and to prevent the working class from turning them

into a struggle for power. It first slandered the students, even when they had become the

principal victims of the police repression, and then did everything possible to isolate the

students and the youth from the striking workers. Wherever possible it controlled the

strike committees to prevent them from becoming instruments of power. The Stalinists

had no intention of leading the working class in revolution and made sure that no one

else should. After carrying out this policy; which opened the way for the resumption of

control of the situation by de Gaulle at the head of a shaken but newly self-confident

bourgeoisie, it had the audacity to claim that there had been a revolutionary situation.

In this the Communist Party stood four square with the Soviet bureaucracy which

feared nothing more than the opening of the European Revolution, for which a successful

revolution in France would have been the prelude. It was clear all along that the CP would

therefore place a brake on the movement while taking care to retain its control over the

working class. Thus the need to discredit the students, to denounce the ‘leftists’, to confine

the aims of the strikes to questions of wages and hours and to bring them to an end as soon

as possible; thus the slogan of a ‘popular government’ and the acceptance of elections which

it knew would be certain to have the form of a referendum for de Gaulle.

The Communist Party has had great difficulty this time in concealing its betrayal

from the workers and from its own militants. The drop in the electoral vote of the

Communist Party indicates this very clearly. Many workers opposed the return to work

to the very end; even more went back reluctantly on the instructions of their leaders

with the knowledge that they had not won the power that was in their grasp. Opposition

in the ranks of the party has never been so widespread; a renewed ferment has begun

amongst the intellectuals but this time it is accompanied to a much greater extent than

before by criticism by worker members. Some sections of the party have been further

astonished by the failure of the CP and the CGT to protest against the banning of the

left-wing organizations and the hounding of their militants.2

1968

Although the elections were run by the Gaullists on a ‘red scare’ platform and with a

lot of anti-Communist talk there can be little doubt that the government, and particularly

de Gaulle himself, are well aware of the services which the CP rendered in May and June.

This was understood during the events by many reporters and commentators of both the

French bourgeois and the foreign press. For the first time, in many papers, the conclusion,

new and astonishing to the writers themselves, that the Communist Party was a great

institution making for the preservation of the bourgeois social order, in other words,’was

a counter-revolutionary force, as Trotsky pointed out over three decades ago, became a

commonplace. As Victor Fay summed it up in Le Monde Diplomatique for July:

‘By putting a brake on the popular upsurge the leaders of the Communist Party

and the CGT upset the vanguard of the working class and cut themselves off from the

revolutionary students. At no moment during the crisis did the CP and the CGT push

the workers towards direct action; they followed rather than led this action. At no time

did they issue a call for a general strike nor recommend the occupation of the factories by

the workers. At no time did they consider the situation as revolutionary. Monsieur Seguy,

general secretary of the CGT declared on June 13: “The question of knowing whether

the hour for the insurrection had struck was never at any time posed before the Bureau

of the Confederation or the Administrative Commission, which are composed, as is well

known, of serious and responsible militants who do not have the reputation of taking

their desires for reality”.’

Whether Seguy is speaking the truth or not is scarcely important. What can be

assumed from the whole behaviour of the CP is that its leaders well knew that a

revolutionary situation did exist. Their main concern was to prevent the working class

pushing towards a seizure of power – a task which they successfully carried out, but only

by dint of immense efforts. After the event they were able to explain that there never had

been a revolutionary situation, in order to cover up their tracks and their actual role in

preventing it from maturing.

Once again, then, as in 1936, as in 1945, as in 1953 and 1958 the Communist Party imposed

a strait-jacket on the working class and helped to preserve the bourgeois social order.

The bitterness and hostility of the attacks launched by the CP on the student

movement and upon the left-wing groups were required in order to prevent the latter

from becoming a pole of attraction and an alternative leadership.

What was the possibility of such an alternative arising? As far as the student

movement was concerned, and those groups who concentrated their main efforts in the

Sorbonne after its liberation from police control on May 13, it can be said that it evaded

in practice such a task. Instead the energies of the students were dispersed in interminable

discussions, sallies to the barricades and occasional sorties to the factory gates.

Only the supporters of the International Committee, the Organisation Communiste

Internationaliste, the youth movement Révoltes and the student movement, the 2

revolution

Fédération des Etudiants Révolutionnaires put forward consistently a Marxist policy.

Themselves taken by surprise by the rapidity with which the storm broke, fighting with

small numbers in a most difficult situation these organisations acquired a valuable capital

of experience in struggle from which the whole international movement can draw.

Undoubtedly their intervention in a number of decisive instances, including the first

occupation at Sud-Aviation, had an important bearing on the course of events. Links were

developed with important sections of the youth and the working class. In the universities

the FER put forward a basically correct line against the advocates of ‘student power’ and

the ‘critical university’ – that is to say against the mainstream of student feeling – with

great consistency and courage in the face of slander and misrepresentation.

In the end the smallness of the vanguard enabled the treachery of the Stalinists and

the reformists to prevail. The alternative leadership, while it made its presence felt, was

not able to take command of the class. Now, along with other left groups, the OCI,

Révoltes and the FER have been banned: but their struggle continues. Inside the CGT

and the CP there is a growing volume of questions and criticism. The workers were not

defeated, and they know it; but the class-conscious elements also know that they could

have gained much more – that power was within their grasp. In these conditions, with the

crisis of French capitalism aggravated by the events of May and June, the opportunities

for intervention, even under conditions of illegality, become very great. The struggle

continues and in the coming period the Trotskyists will come forward to lead the final

victorious struggle of the french working class.

Friday 18 October 2013

Nous sommes tous "Indesirables"

Incredibly, when Mary McCarthy returned from Hanoi to Paris in May 1968, she moved from the cutting edge of anti-imperialist war resistance in SE Asia to the beating heart of anti-capitalist revolution in NW Europe, as instantly as stepping off a plane. And, apparently incredibly 'co-incidentally', one of the key figures in the student/worker rebellion in Paris, Daniel Cohn-Bendit, was the son of German Jewish anti-nazi comrades of Hannah Arendt and Heinrich Blucher in 1930s occupied France. 'Co-incidentally' ? - Non! : Nous Sommes Tous Indesirables'.

Die Welt: What did Hannah Arendt mean to you, when you were still a real,

radical leftist 68er?

radical leftist 68er?

Daniel Cohn-Bendit: That's complicated, because she was a friend of my

parents. I knew her and was aware of her theses as a child. After emigrating

in 1934, she belonged to a group of intellectuals in Paris along with my

parents, Walter Benjamin and Hannah Arendt's husband Heinrich Blücher. My

father and Blücher were interned together at the beginning of the war, and

that resulted in a deep friendship. But you make a point in your question:

Hannah Arendt was not the most influential thinker for me at that time.

parents. I knew her and was aware of her theses as a child. After emigrating

in 1934, she belonged to a group of intellectuals in Paris along with my

parents, Walter Benjamin and Hannah Arendt's husband Heinrich Blücher. My

father and Blücher were interned together at the beginning of the war, and

that resulted in a deep friendship. But you make a point in your question:

Hannah Arendt was not the most influential thinker for me at that time.

Hannah Arendt 1941. Foto: Fred SteinWhen did you meet Hannah Arendt?

When she held a laudatio for Karl Jaspers in 1958, when he received the

Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels. My father had just died and she

visited my mother. The second time I saw her was at the Auschwitz trial in

Frankfurt. I was there with my school class – and she happened to be there

too.

Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels. My father had just died and she

visited my mother. The second time I saw her was at the Auschwitz trial in

Frankfurt. I was there with my school class – and she happened to be there

too.

When did you begin to get interested in Hannah Arendt's work?

In the 1970s, as the discussions about totalitarianism became more and more

pressing. I was a leftist anti-communist and when I came to Germany in 1968,

I was perplexed by the reluctance to compare communism with national

socialism, which was rooted in German history.

pressing. I was a leftist anti-communist and when I came to Germany in 1968,

I was perplexed by the reluctance to compare communism with national

socialism, which was rooted in German history.

Did your referring to Hannah Arendt's "The Origins of Totalitarianism" lead

to conflicts with your colleagues?

to conflicts with your colleagues?

There was conflict from the outset, because when I was expelled from France

in 1968, I was absolutely certain that, despite my revolutionary

convictions, I would prefer to live in West Germany than in the GDR. I saw

in France and the GDR bourgeois societies – that's what we called them back

then – that needed reform but not totalitarian systems.

in 1968, I was absolutely certain that, despite my revolutionary

convictions, I would prefer to live in West Germany than in the GDR. I saw

in France and the GDR bourgeois societies – that's what we called them back

then – that needed reform but not totalitarian systems.

What does Hannah Arendt's still controversial book "Eichmann in Jerusalem"

mean to you?

mean to you?

That the demonisation of the Nazis doesn't help us in the long run. The most

insane thing, that has to be understood is that the Nazis were "normal

people"! Eichmann was a nobody who was only to achieve the status and commit

the annihilation he did in a totalitarian, totally racist system.

insane thing, that has to be understood is that the Nazis were "normal

people"! Eichmann was a nobody who was only to achieve the status and commit

the annihilation he did in a totalitarian, totally racist system.

But some of the claims that Hannah Arendt makes in "Eichmann in Jerusalem"

don't hold up historically. Take for example her complete condemnation of

the Jewish councils...

don't hold up historically. Take for example her complete condemnation of

the Jewish councils...

Daniel Cohn-Bendit facing the police in Nanterre 1968Nonetheless, the

question that she asks with the Jewish council remains relevant: when does

one accept developments and at what point does one put up resistance? It's

possible that Hannah Arendt was not fair on the Jewish councils. But her

basic question is still legitimate: Was it right to collaborate in the first

place? Because it wasn't just the Jews who didn't want to see the

annihilation that was facing them. When the western democracies signed a

treaty with Hitler in Munich in 1938, they didn't see the annihilation

potential that was being developed in Germany. It's basically this question

that is still being asked in Israel. The injustice that Israel is doing to

Palestine is related to the feeling that one doesn't want to ever end up in

the same situation again. That's a problem that, in my opinion, has not been

dealt with adequately – but it's a real problem.

question that she asks with the Jewish council remains relevant: when does

one accept developments and at what point does one put up resistance? It's

possible that Hannah Arendt was not fair on the Jewish councils. But her

basic question is still legitimate: Was it right to collaborate in the first

place? Because it wasn't just the Jews who didn't want to see the

annihilation that was facing them. When the western democracies signed a

treaty with Hitler in Munich in 1938, they didn't see the annihilation

potential that was being developed in Germany. It's basically this question

that is still being asked in Israel. The injustice that Israel is doing to

Palestine is related to the feeling that one doesn't want to ever end up in

the same situation again. That's a problem that, in my opinion, has not been

dealt with adequately – but it's a real problem.

Monday 14 October 2013

Sunday 13 October 2013

Saturday 12 October 2013

" I am assaulted by clippings about The Group..."

Hotel Lucia

Madrid

Saturday (10/19/63)

Dearest Hannah

...The whole Eichmann business is terrible. Now the English reviews. Jim has sent me here crossman and Trevor-Roper. But he has also told me on the phone that there was a very good one, in every sense, by A Alvarez in the New Statesman...

141 Rue de Rennes

Paris 6

October 24, 1963

...In Paris I am assaulted by clippings about The Group, many of them terribly hostile, and by requests for interviews and photos...And I confess I'm depressed by what seems to me the treachery of the New York Book Review people. I suppose you saw the Mailer piece and the parody that preceded it. I find it strange that people who are supposed to be my friends should solicit a review from an announced enemy...It parallels, as I foresaw, in a small way the Eichmann furore, but seems to lack even the hypocritical justification that Jewish piety there provided...

Mary

Quadrangle Club

1155 West 57th

Chicago 37 Illinois

(Autumn 1963)

Dearest Mary

....I read Mailer's review only a couple of days ago - it is so full of personal and stupid invectives (stupid means vulgar) that I can't understand how or why they printed it. I am afraid that Elizabeth had the brilliant idea to ask him - just as she had the brilliant idea to ask Abel to do the PR piece...But she would probably not have done either if there had not been fertile ground for precisely this stab in the back. And what surprises and shocks me most is the tremendous amount of hatred and hostility lying around and waiting only for a chance to break out...

Much, much love

Yours,

Hannah

Madrid

Saturday (10/19/63)

Dearest Hannah

...The whole Eichmann business is terrible. Now the English reviews. Jim has sent me here crossman and Trevor-Roper. But he has also told me on the phone that there was a very good one, in every sense, by A Alvarez in the New Statesman...

141 Rue de Rennes

Paris 6

October 24, 1963

...In Paris I am assaulted by clippings about The Group, many of them terribly hostile, and by requests for interviews and photos...And I confess I'm depressed by what seems to me the treachery of the New York Book Review people. I suppose you saw the Mailer piece and the parody that preceded it. I find it strange that people who are supposed to be my friends should solicit a review from an announced enemy...It parallels, as I foresaw, in a small way the Eichmann furore, but seems to lack even the hypocritical justification that Jewish piety there provided...

Mary

Quadrangle Club

1155 West 57th

Chicago 37 Illinois

(Autumn 1963)

Dearest Mary

....I read Mailer's review only a couple of days ago - it is so full of personal and stupid invectives (stupid means vulgar) that I can't understand how or why they printed it. I am afraid that Elizabeth had the brilliant idea to ask him - just as she had the brilliant idea to ask Abel to do the PR piece...But she would probably not have done either if there had not been fertile ground for precisely this stab in the back. And what surprises and shocks me most is the tremendous amount of hatred and hostility lying around and waiting only for a chance to break out...

Much, much love

Yours,

Hannah

Wednesday 9 October 2013

"the ordinariness of Eichmann is... a faithful description of a phenomenon"

|

Miriam Chiaromonte, Czeslaw Milosz, and Mary McCarthy |

Bocca di Magra

September 24, 1963

Dearest Hannah

....Nicola (Chiaromonte) feels that the issues raised by your book ought to be discussed. Not the debater's points 'scored' by Lionel (Abel) but the implications of your views about the role played by the Jewish Councils - that is, what is implied about organisations in modern society generally. He would also like to know why you think the Nazis failed in their anti-semitic (sic) program in Denmark, Bulgaria and Italy - this apart from the presence or absence of Jewish Councils and from the sheer facts as you give them. Can a common factor be found to explain this? For if there is such a common factor, it ought to be cultivated and safeguarded by humanity for future emergencies. Or is there no such thing? Was it in some way random - here the personal courage of a king, there the natural easygoingness and humane realism of an old people (the Italians) etc? And he would like to see you develop your basic notion of the ordinariness of Eichmann. What does this mean? If not the naive formulation that "there is a little Eichmann in all of us," then what? He thinks he agrees with what you are saying but he is not sure he has understood you. Of course, the idea of sustaining such a discussion in the atmosphere created by Lionel and thousands of preaching rabbis is somewhat farfetched perhaps. But perhaps just such a discussion, pursued in a thoughtful way, would be the necessary and in a way the only answer to what you call the mobilization of the mob...

Mary

The University of Chicago

Chicago 37, Illinois

Committee on Social Thought

October 3. 1963

Dearest Mary

....Let me answer your letter as briefly as possible. I am convinced that I should not answer individual critics. I probably shall finally make, not an answer, but a kind of evaluation of this whole strange business. This, I think, should be done after the furore has run its course...If you were here you would understand that this whole business, with few exceptions, has absolutely nothing to do with criticism or polemics in the normal sense of the word. It is a political campaign, led and guided in all particulars by interest groups and governmental agencies. It would be foolish for me, but not for others, to overlook this fact. The criticism is directed at an 'image' and this image has been substituted for the book I wrote...

...To repeat: the question of Jewish resistance substitutes for the real issue, namely, that individual members of the Jewish councils had the possibility not to participate. Or: 'A Defence of Eichmann,' which I supposedly wrote, is a substitution for the real issue: what kind of man was the accused and to what extent can our legal system take care of these new criminals who are not ordinary criminals?

As to the points Nicola made: my book is a report and therefore leaves all questions of why things happened out of account. I describe the role of the Jewish councils. It was neither my intention nor my task to explain this whole business - either by reference to Jewish history or by reference to modern society in general. I, too, would like to know why countries so unlike each other as Denmark, Italy and Bulgaria saved their Jews. My 'basic notion' of the ordinariness of Eichmann is much less a notion than a faithful description of a phenomenon. I am sure there can be drawn many conclusions from this phenomenon and the most general I drew is indicated 'the banality of evil.' I may sometime want to write about this, and then I would write about the nature of evil. but it would have been entirely wrong of me to do it within the framework of the report...

Yours,

Hannah

|

Monday 7 October 2013

" What a risky business to tell the truth on a factual level without theoretical or scholarly embroidery."

New York

September 16, 1963

Dearest Mary

....Why did I not write earlier? Well, the truth of the matter is that I did not "feel fine". Heinrich has not been well, he is much better now, working as usual etc, but I am deeply worried and quite unhappy that I have to go to Chicago. (But please, let that remain entre nous.) We have been together for 28 years and life without him would be unthinkable. Add to this the Eichmann trouble which i try to keep from him as much as I possibly can - and you will understand why I am in no mood for writing. You probably know that PR have turned against me in a rather vicious manner(Lionel Abel who anyhow goes around town spreading slander about myself as well as Heinrich) and generally, one can say that the mob - intellectual or otherwise - has been successfully mobilised. I just heard that the Anti-Defamation League has sent out a circular letter to all rabbis to preach against me on New Year's Day. well, I suppose this would not disturb me unduly if everything else were all right, But, worried as I am, I can no longer trust myself to keep my head and not to explode. What a risky business to tell the truth on a factual level without theoretical or scholarly embroidery. This side of it, I admit, I do enjoy; it taught me a few lessons about truth and politics...

Much love, yours

Hannah

|

| Lionel Abel (standing) with the PR gang |

Bocca Di Magra

September 24, 1963

Dearest Hannah

...I want to help you in some way and not simply by being an ear. What can be done about this Eichmann business, which is assuming the proportions of a pogrom. Whether you answer or not...I am going to write something to the boys for publication

...the issues raised by your book ought to be discussed...about the role played by the Jewish Councils... Of course the idea of sustaining a discussion in the atmosphere created by Lionel and the thousands of preaching rabbis is somewhat far fetched perhaps. But perhaps such a discussion...(is) the only answer to the mobilization of the mob...

...My deepest love to you and tight embraces,

Mary

"...They hanged Eichmann yesterday..."

8 Rue de la Chaise

Paris

June 1, 1962

Dearest Hannah

....They hanged Eichmann yesterday, my reaction was curious, rather shrugging, "Well, one more life - what difference does it make?" This cannot be the reaction the Israelis desired, yet short of rejoicing in his death, on the one hand, or being angry at it on the other, what else can the ordinary person feel? To execute a man and excite a reaction of indifference is to bring people too close to the way the Nazis felt about human life - "One more gone"....Anyway, how is your piece coming?....

....All my love to you and love to Heinrich and write fairly soon.

Mary

New York

June 7, 1962

Dearest Mary -

.....I am still in Eichmann, have the portrait part almost finished- or so I hope. It is much longer than i thought, about 80 pages now. If I am lucky, it will not be over 160 pages. I am still glad I did it, despite the staggering amount of sheer labor that has to go into it. My room looks like a battlefield with papers and the mimeographed sheets of the trial transcripts strewn all over the place...

Love and yours,

Hannah

Thursday 3 October 2013

Bloggerlees makes Personal Appearance Shock Horror

At Manchester's Cornerhouse

Hannah Arendt

12A- Margarethe von Trotta

- In English, French, German

- 113 mins

Hannah Arendt looks at the life of the influential German-Jewish philosopher and political theorist. In 1961, Arendt reported for the New Yorker on the war crimes trial of Nazi SS lieutenant colonel Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. Her articles, which introduced the now-famous concept of the banality of evil, triggered unprecedented controversy with Jewish public figures and even some of Hannah’s friends, who accused her of rationalising Nazi barbarism. Using footage from the Eichmann trial and weaving a narrative that spans three countries, Margarethe von Trotta has created an engaging and highly dramatic film.

Event

The 18:05 screening of Hannah Arendt on Tue 8 October will be accompanied by a free post-screening discussion led by Dr Andy Willis, Dr Shivani Pal and Richard Lees. This discussion will explore the legacy of Hannah Arendt’s ideas with regard to international justice and human rights, and we’ll also examine the portrayal of Hannah Arendt and Mary McCarthy in this film.

More Info

Cast: Barbara Sukowa, Axel Milberg, Janet McTeer

Country: Germany, Luxemburg, France

Year: 2012

Subtitles

Country: Germany, Luxemburg, France

Year: 2012

Subtitles

Screening times

- FRI 27

SEP17:3020:20 - SAT 28

SEP14:0017:30 - SUN 29

SEP14:1020:20 - MON 30

SEP17:30 - TUE 01

OCT17:30 - WED 02

OCT14:0020:20 - THU 03

OCT14:0017:30

- FRI 04

OCT13:20 - SAT 05

OCT18:0020:25 - SUN 06

OCT15:4520:25 - MON 07

OCT20:25 - TUE 08

OCT18:0520:25 - WED 09

OCT15:4520:25 - THU 10

OCT15:4520:25

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)